BACK TO finalistS

Finalist: Interior Design

THE POETICS OF FORM

a room for “weaving” our life In modern Japan, despite high literacy rates, many people remain invisible and voiceless. Elderly individuals, non-regular workers, single parents, immigrants, LGBTQ+ persons, and people with disabilities are often marginalized—not only economically or institutionally, but spatially and emotionally. Their lives are fragmented by labor and caregiving, leaving them with little […]

a room for “weaving” our life

In modern Japan, despite high literacy rates, many people remain invisible and voiceless. Elderly individuals, non-regular workers, single parents, immigrants, LGBTQ+ persons, and people with disabilities are often marginalized—not only economically or institutionally, but spatially and emotionally. Their lives are fragmented by labor and caregiving, leaving them with little time, space, or community in which to reflect or be heard.

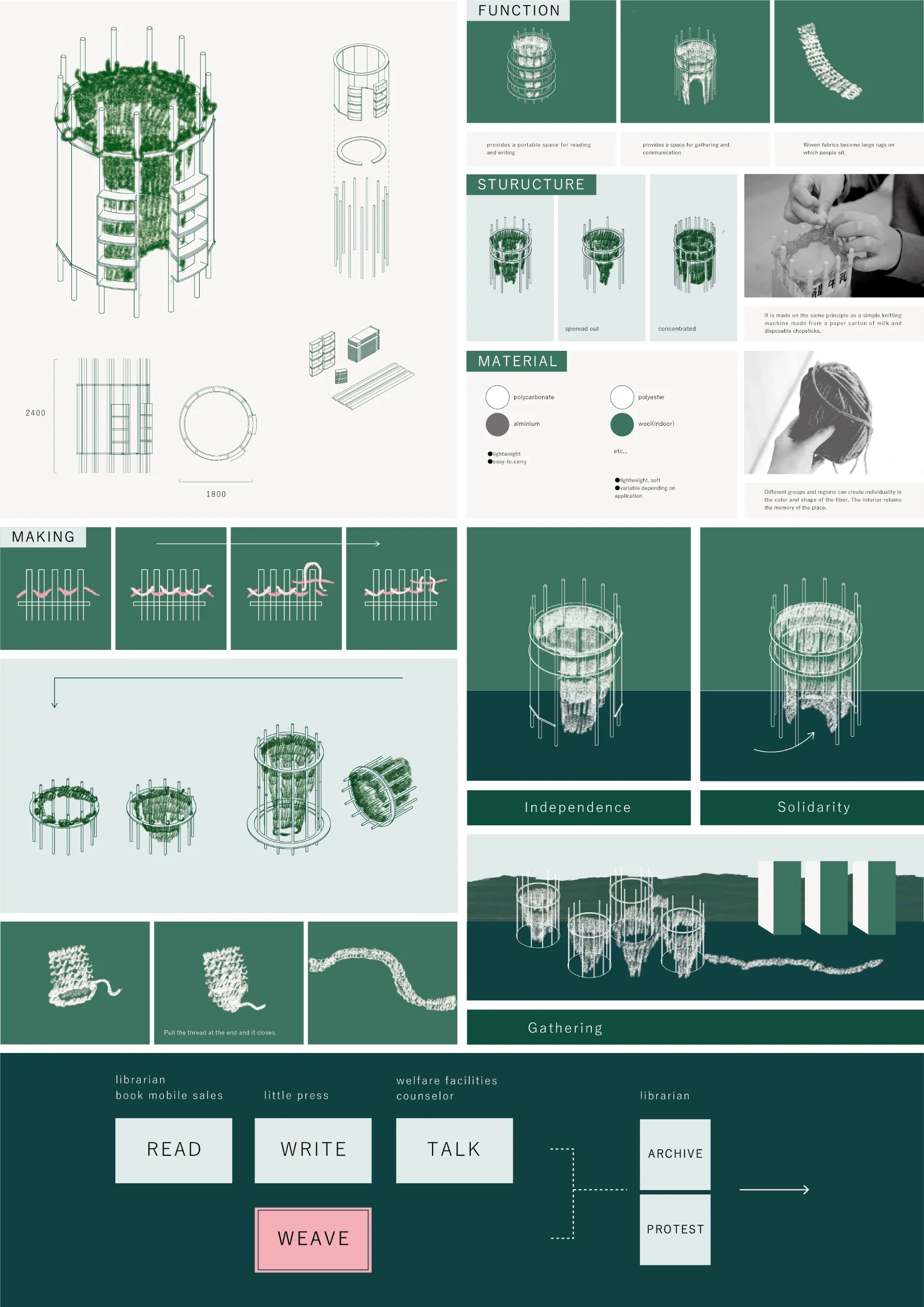

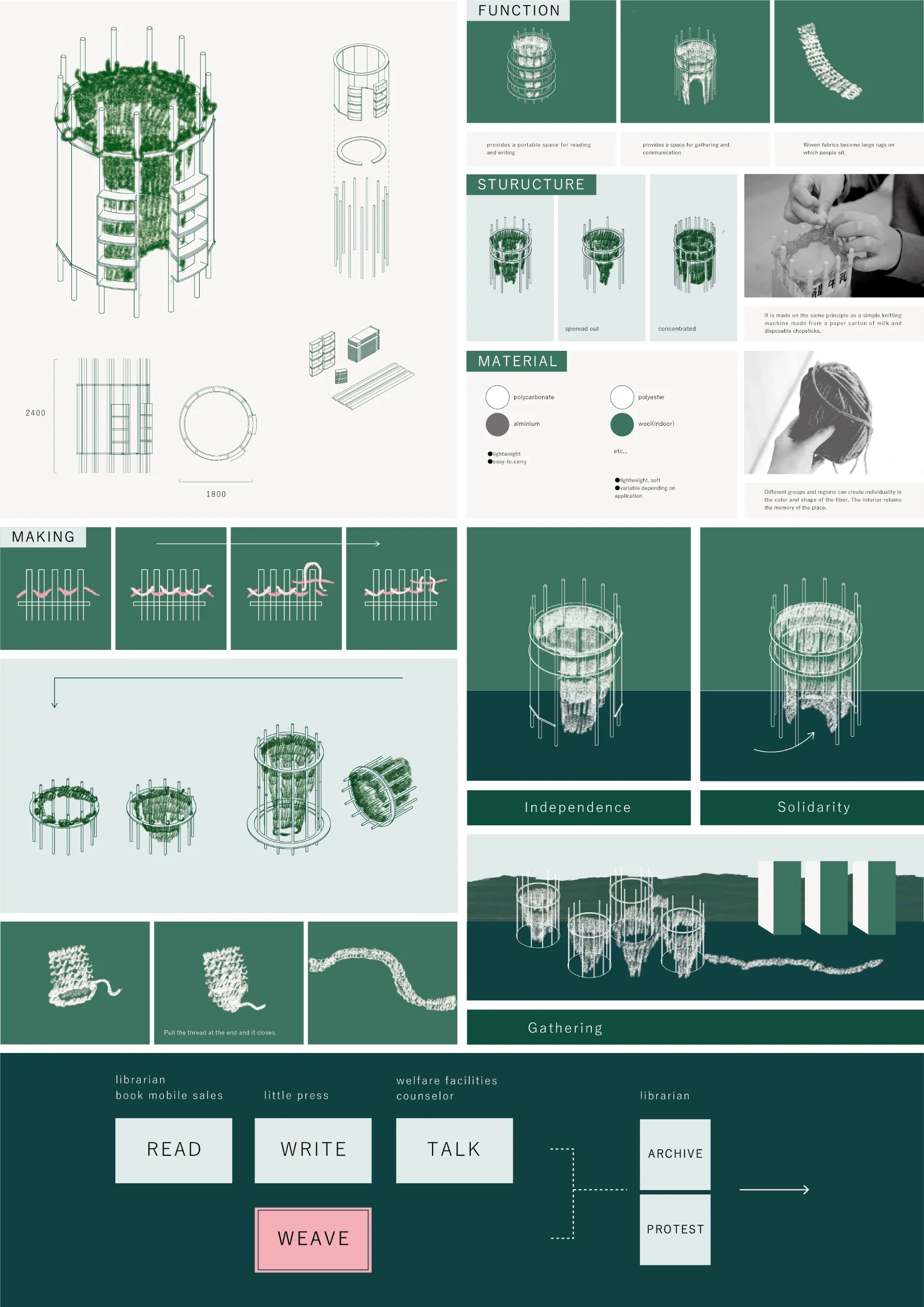

This project proposes an interior—a soft architecture—for people who are usually excluded from the architectural imagination. It is a space not built by professionals for passive users, but one that can be made by the people themselves, using simple tools and slow, repeated actions. The aim is to create a place where people can read, write, or simply sit in silence—a space for archiving ordinary lives.

The conceptual starting point is twofold: First, Virginia Woolf’s assertion in A Room of One’s Own that a woman needs “money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Second, Kazuko Tsurumi’s “Life Writing Movement,” in which ordinary housewives gathered in postwar Japan to document their daily lives in their own words. These two visions—solitude and collectivity—are not contradictory, but complementary. To write is to reflect, but also to connect. The design seeks to spatialize both gestures.

The architectural form is inspired by a children’s knitting toy, used to make cord by looping yarn through a circular frame. Here, a similar technique is scaled up: yarn is woven between vertical poles and a wooden frame, gradually building up a tubular, fabric-like enclosure. This creates a space that is both inside and outside—a room with soft, stretchable walls. The woven threads define the boundary, but gently, allowing light, air, and sound to filter through. The outer frame provides a space for shared activity and connection; the woven interior creates a cocoon for solitude and contemplation.

The process of making this space is as important as the space itself. Like textile work, it is accumulative, repetitive, and low-barrier. It does not require technical expertise or financial power—only time, intention, and community. People can build their own “rooms” at their own pace, with their own colors and textures, according to the needs of their bodies and environments. In this way, the space remains flexible, portable, and personal.

Examples of use include:

This is not architecture as monument, but as memory. Not a structure that asserts permanence, but one that archives impermanence. The woven room becomes a living document—of labor, care, creativity, and connection.

Ultimately, architecture and interior design have the power not only to house people, but to reveal their presence. A closed room can be a sanctuary, but a woven room is a gesture: it says “I am here,” softly but clearly, in a world where many lives remain unheard. By offering a way to craft one's own space—and leave a trace of one's own life—it becomes a tool for quiet empowerment, and a collective act of remembering.

Showcase your design to an international audience

SUBMIT NOW

Image: Agrapolis Urban Permaculture Farm by David Johanes Palar

Top

a room for “weaving” our life In modern Japan, despite high literacy rates, many people remain invisible and voiceless. Elderly individuals, non-regular workers, single parents, immigrants, LGBTQ+ persons, and people with disabilities are often marginalized—not only economically or institutionally, but spatially and emotionally. Their lives are fragmented by labor and caregiving, leaving them with little time, space, or community in which to reflect or be heard. The process of making this space is as important as the space itself. Like textile work, it is accumulative, repetitive, and low-barrier. It does not require technical expertise or financial power—only time, intention, and community. People can build their own “rooms” at their own pace, with their own colors and textures, according to the needs of their bodies and environments. In this way, the space remains flexible, portable, and personal. Examples of use include: This is not architecture as monument, but as memory. Not a structure that asserts permanence, but one that archives impermanence. The woven room becomes a living document—of labor, care, creativity, and connection.

This project proposes an interior—a soft architecture—for people who are usually excluded from the architectural imagination. It is a space not built by professionals for passive users, but one that can be made by the people themselves, using simple tools and slow, repeated actions. The aim is to create a place where people can read, write, or simply sit in silence—a space for archiving ordinary lives.

The conceptual starting point is twofold: First, Virginia Woolf’s assertion in A Room of One’s Own that a woman needs “money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Second, Kazuko Tsurumi’s “Life Writing Movement,” in which ordinary housewives gathered in postwar Japan to document their daily lives in their own words. These two visions—solitude and collectivity—are not contradictory, but complementary. To write is to reflect, but also to connect. The design seeks to spatialize both gestures.

The architectural form is inspired by a children’s knitting toy, used to make cord by looping yarn through a circular frame. Here, a similar technique is scaled up: yarn is woven between vertical poles and a wooden frame, gradually building up a tubular, fabric-like enclosure. This creates a space that is both inside and outside—a room with soft, stretchable walls. The woven threads define the boundary, but gently, allowing light, air, and sound to filter through. The outer frame provides a space for shared activity and connection; the woven interior creates a cocoon for solitude and contemplation.

Ultimately, architecture and interior design have the power not only to house people, but to reveal their presence. A closed room can be a sanctuary, but a woven room is a gesture: it says “I am here,” softly but clearly, in a world where many lives remain unheard. By offering a way to craft one's own space—and leave a trace of one's own life—it becomes a tool for quiet empowerment, and a collective act of remembering.