BACK TO finalistS

Finalist: Architectural Category

BEEJ (A TRANSITORY INTERFACE)

Beej / Seed (a transitory interface) The idea finds its roots in the memory of my great-grandmother, who first taught me to see the seed not merely as something that grows, but as something sacred—something to protect. She once told me how, during a famine, her mother hid bajra seeds in the folds of her […]

Beej / Seed (a transitory interface)

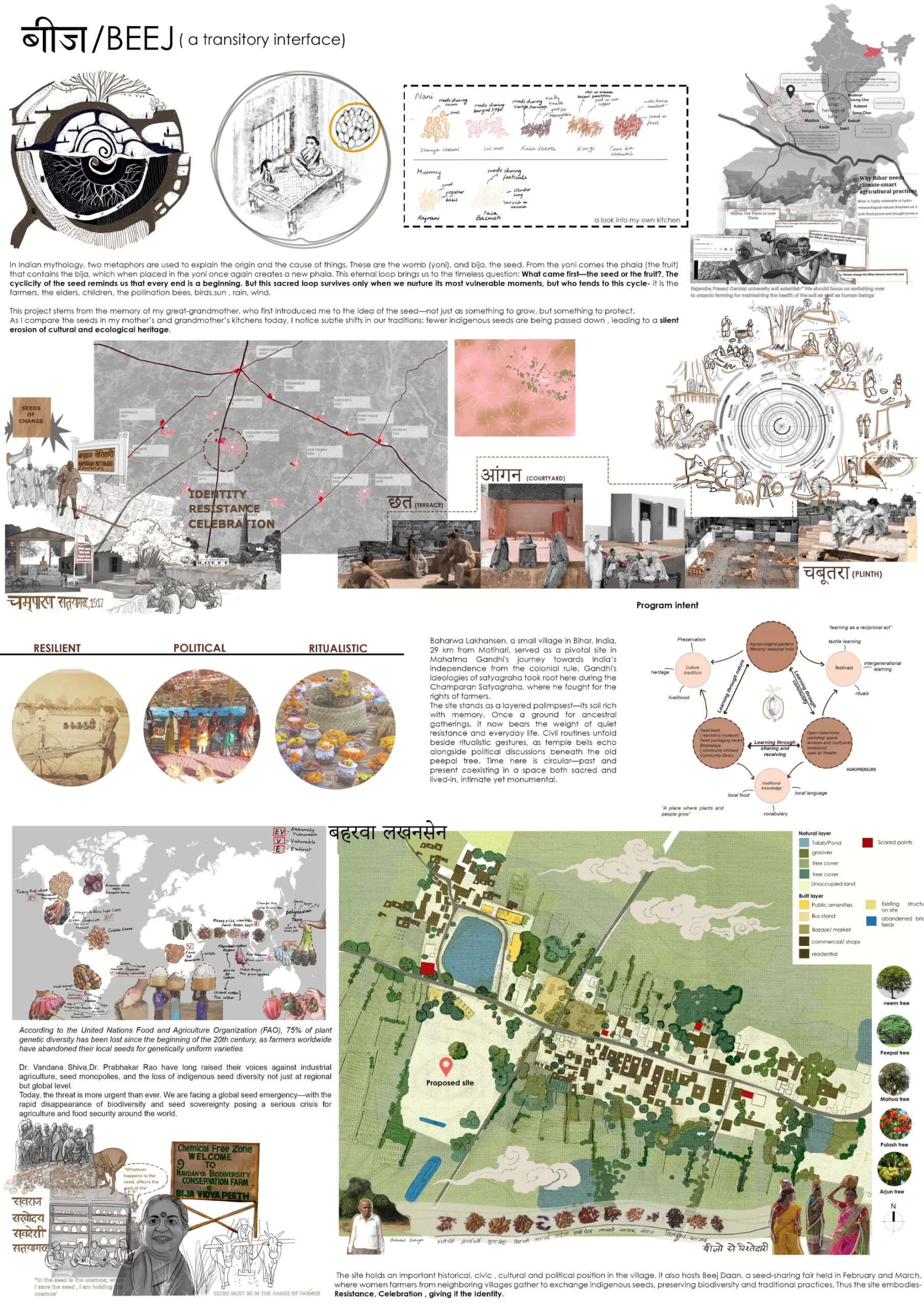

The idea finds its roots in the memory of my great-grandmother, who first taught me to see the seed not merely as something that grows, but as something sacred—something to protect. She once told me how, during a famine, her mother hid bajra seeds in the folds of her saree, knowing that losing them meant losing the next season’s hope.

Through such quiet acts of care—in kitchens filled with stories—I began to see how seeds hold memory. Comparing the seeds in my mother’s and grandmother’s kitchens today, I notice subtle shifts: fewer indigenous varieties are passed down, revealing a silent erosion of cultural and ecological heritage.

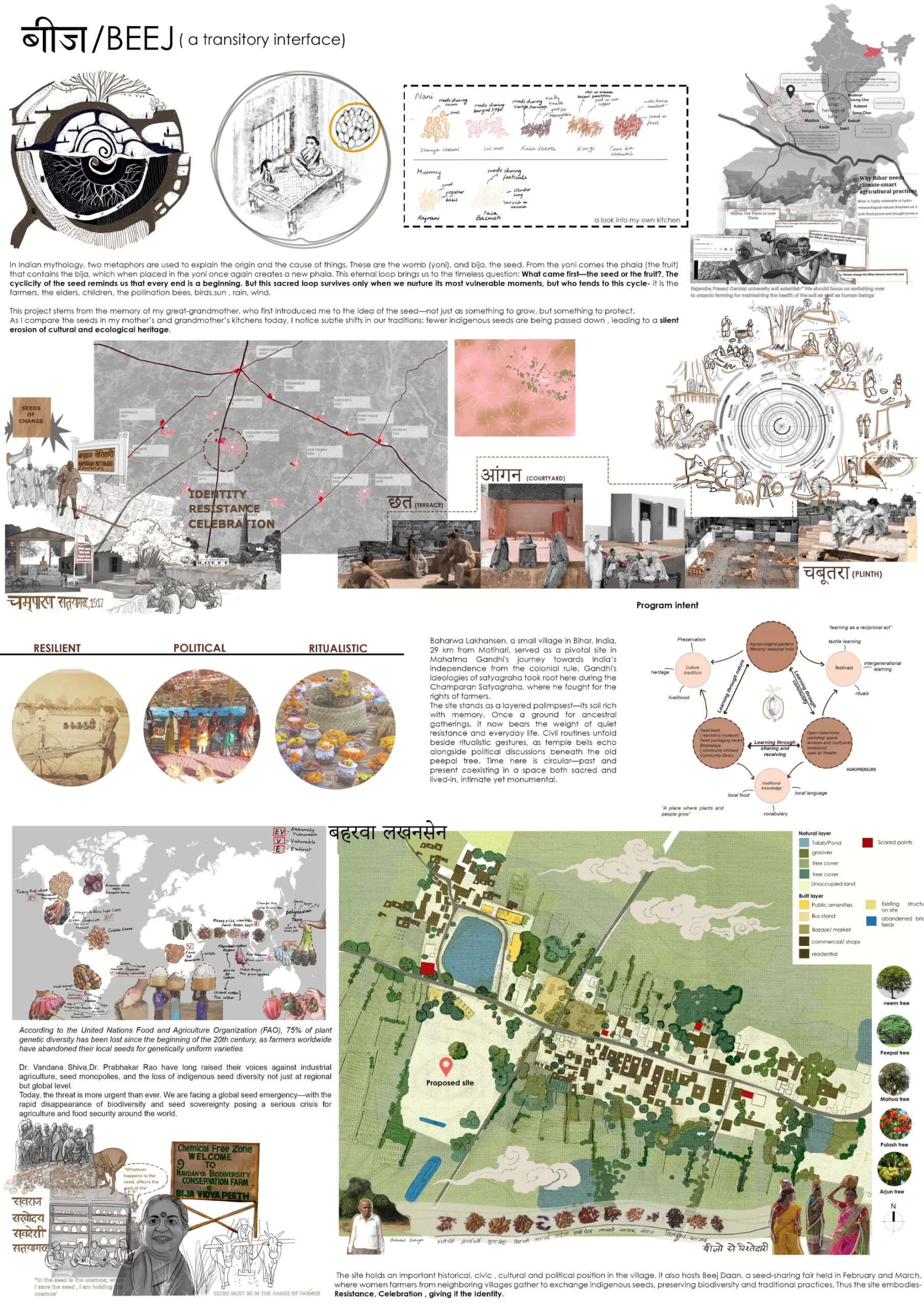

In Indian mythology, two metaphors explain the origin of life: the womb (yoni) and the seed (bija). The fruit (phala) carries the seed, which begins the cycle again—a never-ending loop of life. But this cycle survives only through care. It is the community—farmers, elders, seed keepers, and children—who protect it, alongside quiet allies like bees, microbes, wind, and rain.

According to the UN FAO, 75% of plant genetic diversity has been lost since the early 20th century, as industrial seed systems replace local varieties. Experts like Dr. Vandana Shiva and Dr. Prabhakar Rao have long warned against this monoculture, emphasizing the urgency of protecting biodiversity and seed sovereignty.

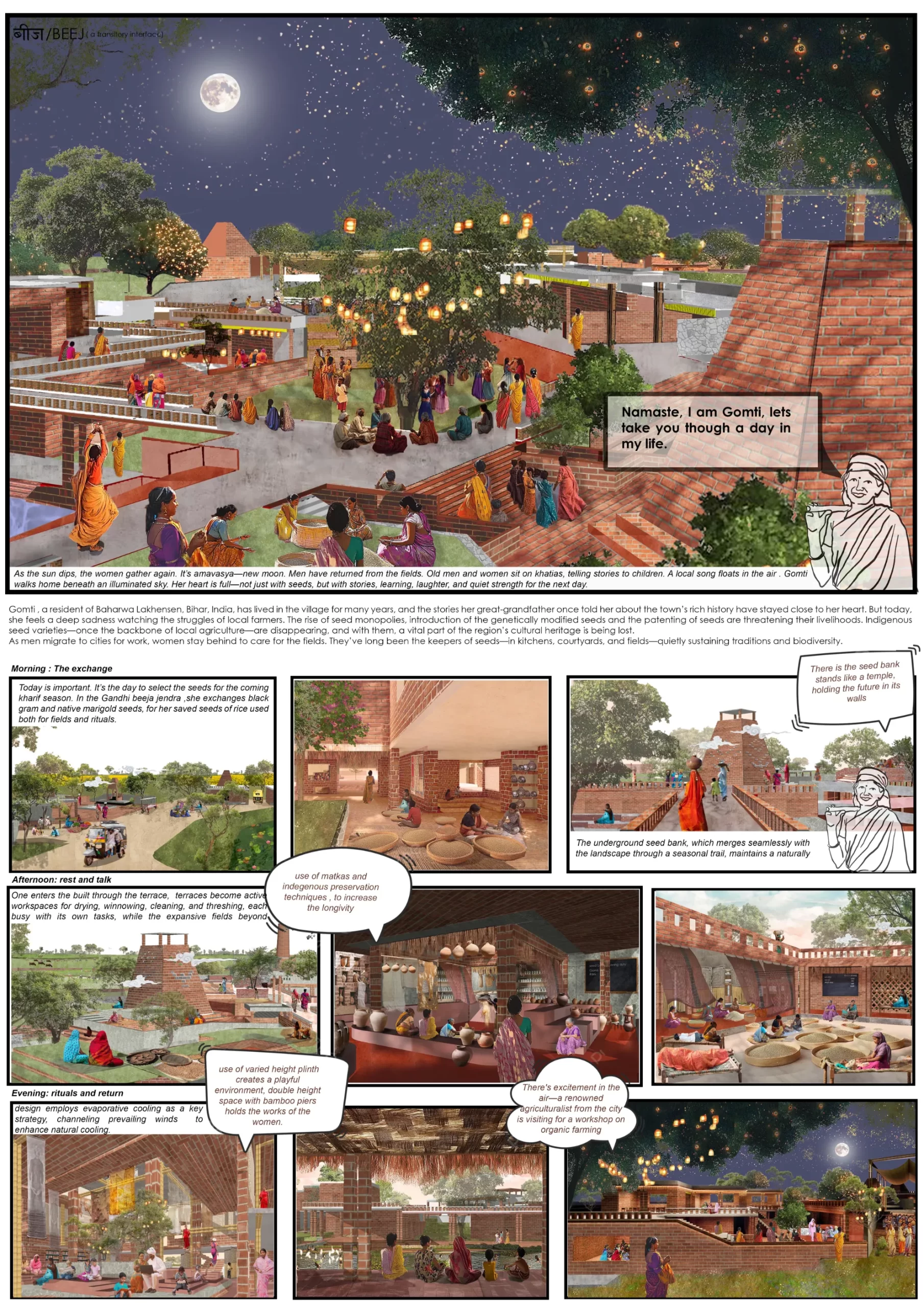

Baharwa Lakhansen, a small village in Bihar, 29 km from Motihari, played a pivotal role in Gandhi’s Champaran Satyagraha. Today, it is witnessing a different struggle—the disappearance of farmer-saved seeds under the growing dominance of corporations like Monsanto. This loss threatens not just biodiversity, but also the traditional knowledge, rituals, and language embedded in these seeds.

Yet resistance endures. Every February and March, the village hosts Beej Daan, a seed-sharing fair where women farmers from neighboring villages exchange indigenous seeds—preserving biodiversity and tradition through collective action. The site becomes an embodiment of identity, celebration, and resistance, and the architectural intervention plays a vital role in giving it the recognition it deserves.

Design Intent: Architecture Rooted in Memory and Ecology

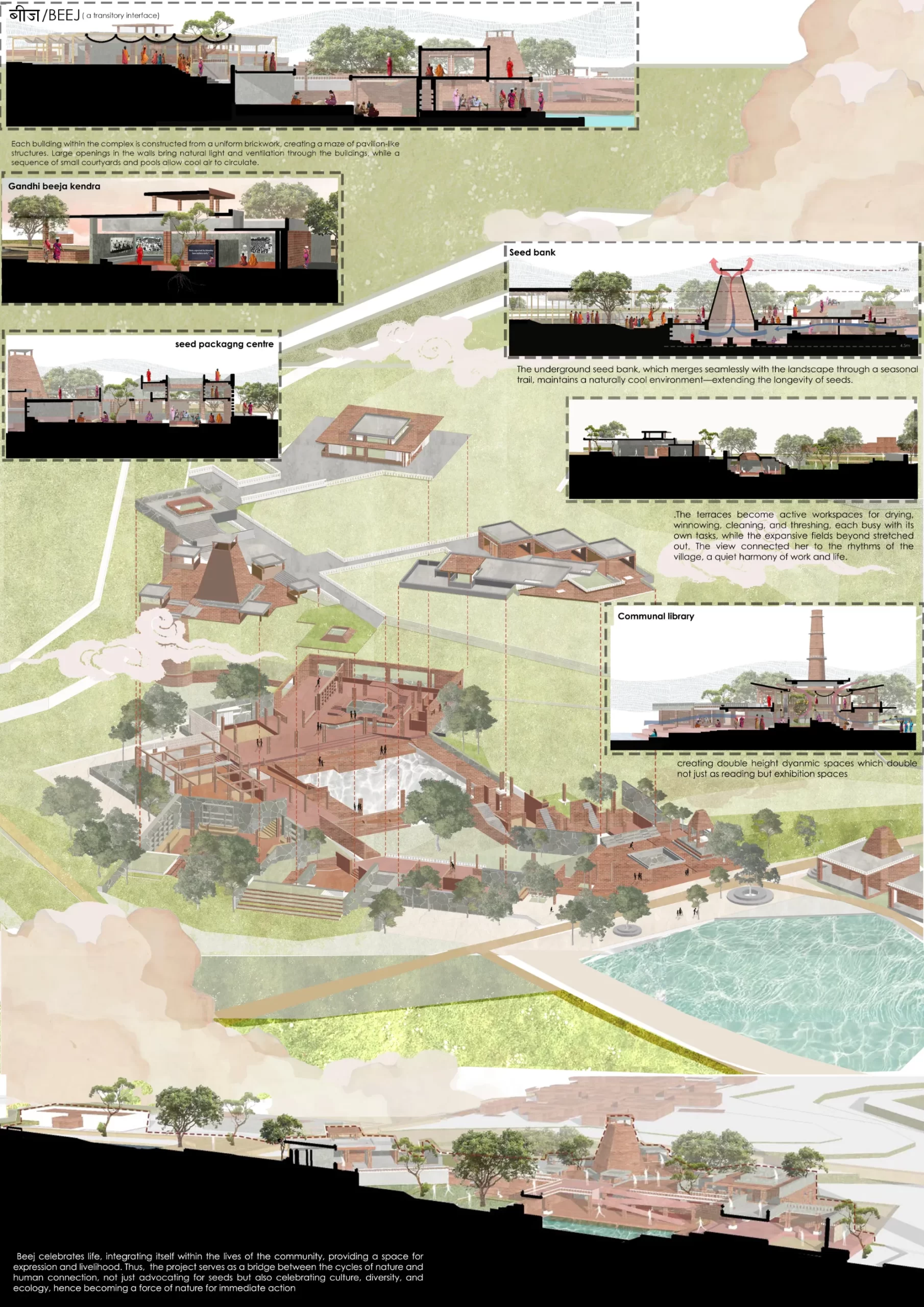

The program reimagines learning as a reciprocal act—through a seed bank, communal kitchen, and library. Learning happens not in isolation, but through shared spaces like terraces, courtyards, open classrooms, and workshop areas. Nature becomes a co-teacher—through agro-ecological gardens and seasonal trails that shift with time.

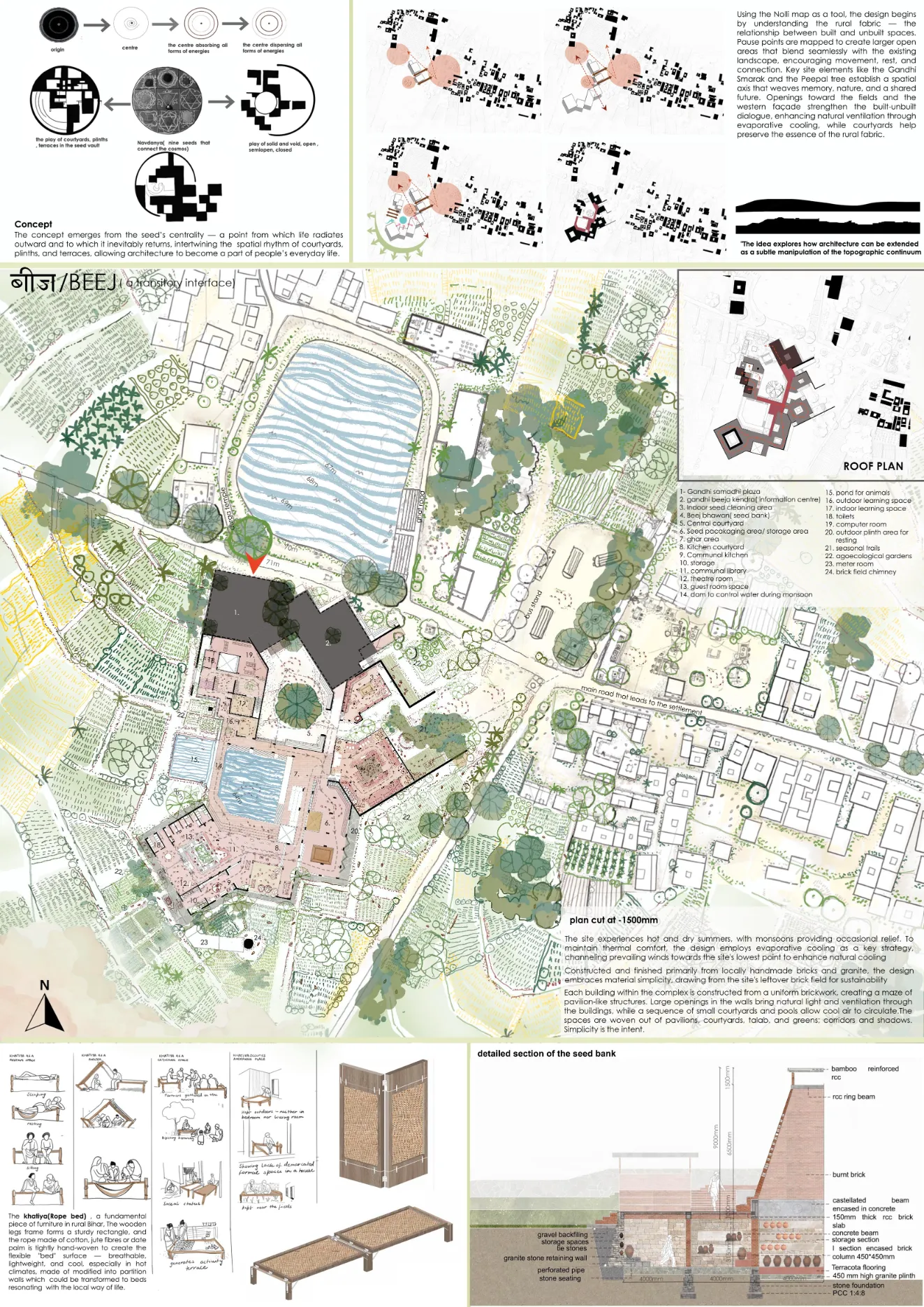

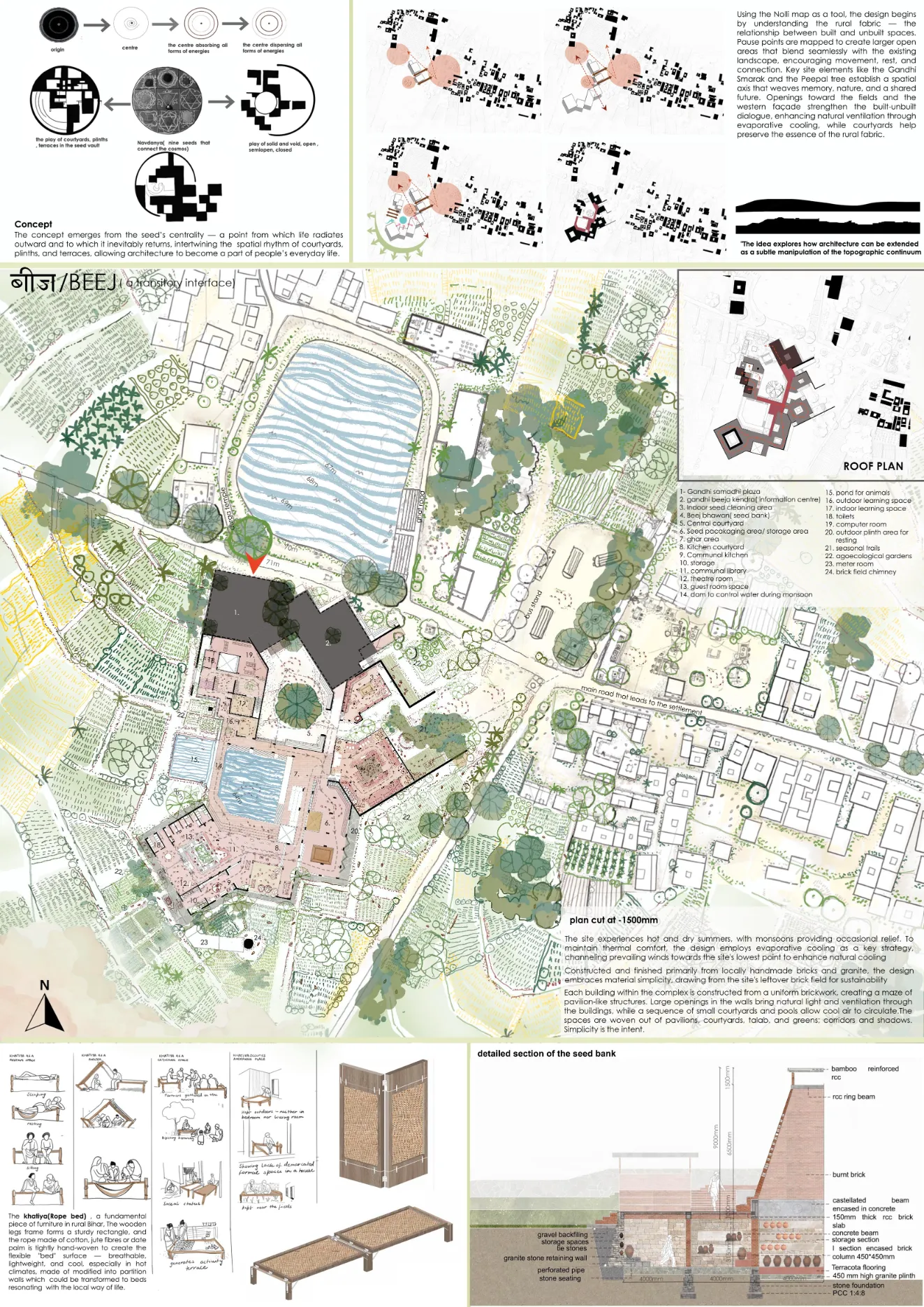

The design investigates how a place is shaped by collective memory—how architecture becomes activism, dispersing the act of saving and sharing throughout India. Using the Nolli map as a tool, the design begins with an understanding of the rural fabric—the relationship between built and unbuilt. Key pause points and natural site markers like the Peepal tree and Gandhi Smarak establish a spatial axis connecting memory, ecology, and community. Open spaces blend with the existing landscape, encouraging movement, pause, and interaction, while extending towards the fields yet retaining a central connection to the Peepal tree.

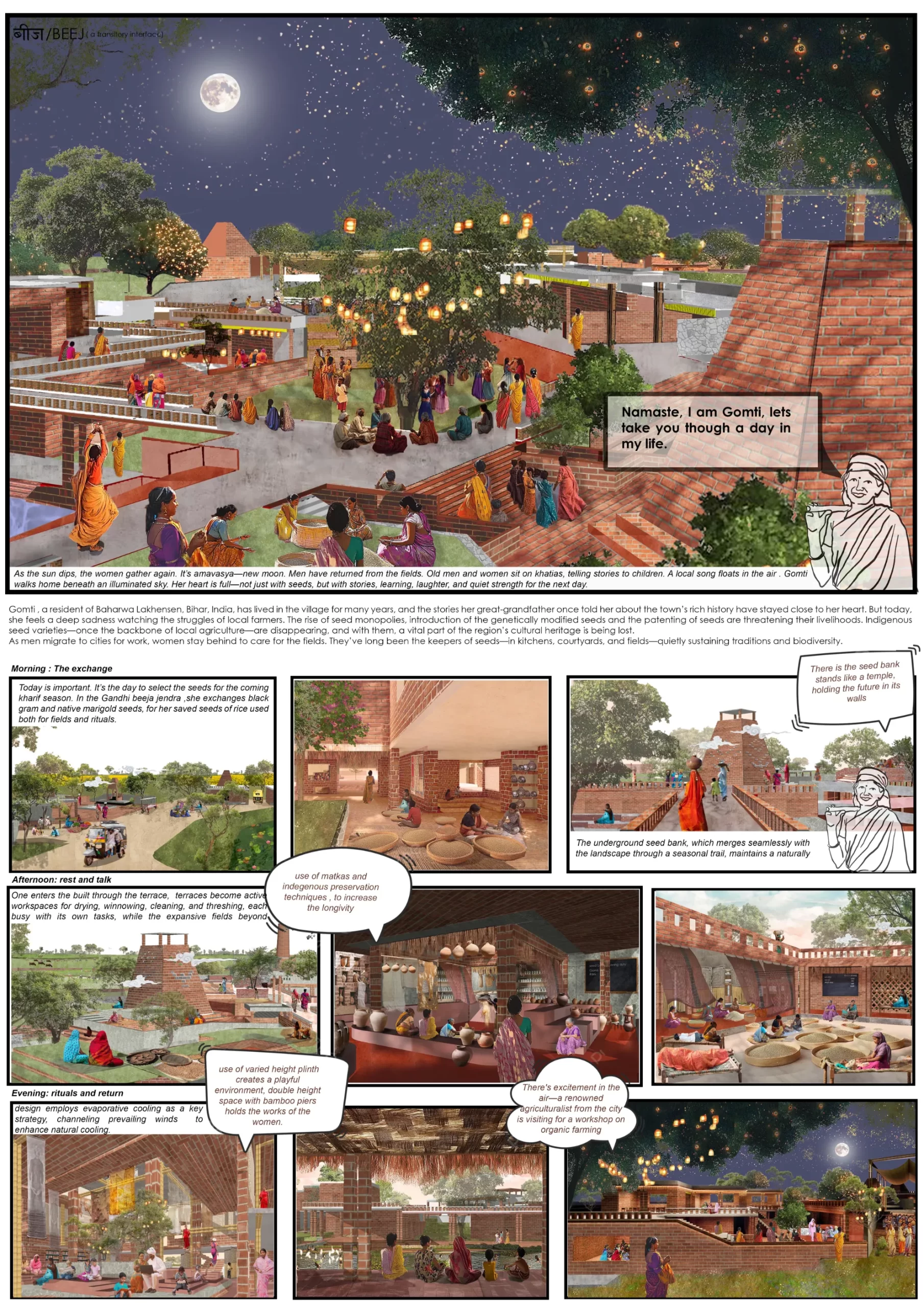

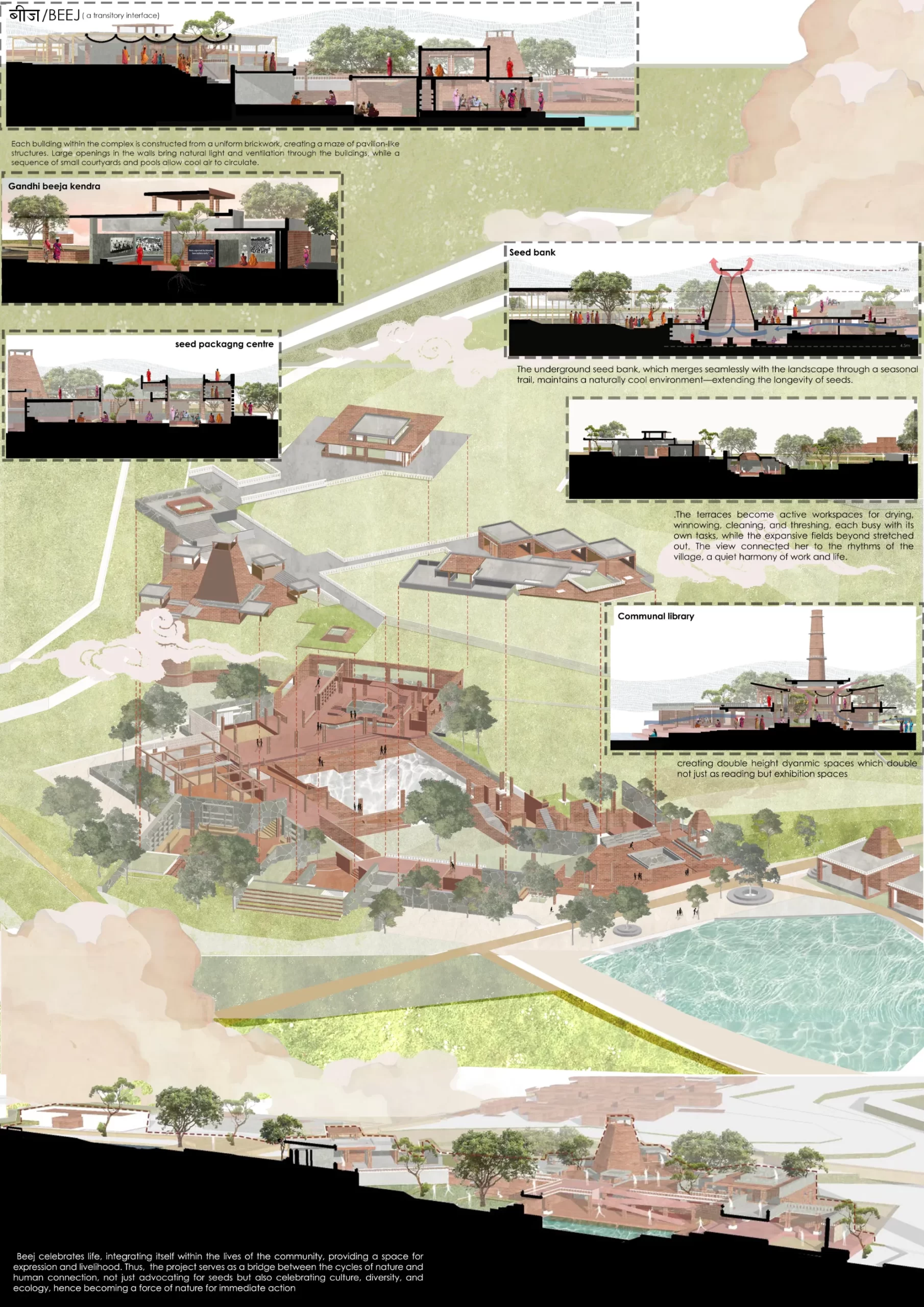

The project explores the interplay of solid and void through courtyards, plinths, and terraces, drawing from the rhythms of local architecture. Terraces function as essential social and working spaces—used for drying seeds, winnowing, and communal gathering. A play of levels creates visual and physical connections, encouraging movement and interaction. The central courtyard serves as a vibrant gathering space, hosting celebrations and fostering community interaction showing the adaptability of the spaces. The use of varied height plinth creates a playful environment, double height space with bamboo piers holds the works of the women.

The seed bank, envisioned as a temple, unfolds along a pradakshina path around the sacred Peepal tree —symbolizing the continuity of life. Merging into the landscape via a seasonal trail, the underground seed bank uses natural cooling to extend seed longevity. Edge conditions serve as vital thresholds, revealing human-ecosystem relationships. The lake edge, for example, transforms into a vibrant market space-becoming a key site of interaction.

Passive strategies—green roofs, stack effect, evaporative cooling, and locally sourced materials—anchor the project in sustainability. Bricks salvaged from an old brick kiln on site carry material memory and reduce embodied energy. The khatiya, a familiar wooden bed woven with jute or cotton fiber, is adapted into partition walls that can transform into sleeping surfaces—rooting the architecture in local practice.

A study of indigenous seed preservation revealed deeply communal, low-tech methods: matkas (terracotta pots), neem treatment, ash coating, bamboo containers sealed with mud and cow dung. Terracotta flooring keeps interiors naturally cool, reinforcing a sustainable, context-sensitive design approach. Spaces are woven out of pavilions, courtyards, talabs, and gardens—stitched together through corridors and shadows. Architecture, here, does not dominate the land but becomes it extending the topography rather than altering it.

Beej becomes a living archive—a space of expression, livelihood, and memory. It bridges the cycles of nature and human connection, celebrating not only seeds but also culture, diversity, and ecology. As such, it acts not only as a regional intervention but as a global call for action—a force of nature in itself.

Showcase your design to an international audience

SUBMIT NOW

Image: Agrapolis Urban Permaculture Farm by David Johanes Palar

Top

Beej / Seed (a transitory interface) The idea finds its roots in the memory of my great-grandmother, who first taught me to see the seed not merely as something that grows, but as something sacred—something to protect. She once told me how, during a famine, her mother hid bajra seeds in the folds of her saree, knowing that losing them meant losing the next season’s hope. Design Intent: Architecture Rooted in Memory and Ecology The program reimagines learning as a reciprocal act—through a seed bank, communal kitchen, and library. Learning happens not in isolation, but through shared spaces like terraces, courtyards, open classrooms, and workshop areas. Nature becomes a co-teacher—through agro-ecological gardens and seasonal trails that shift with time.

Through such quiet acts of care—in kitchens filled with stories—I began to see how seeds hold memory. Comparing the seeds in my mother’s and grandmother’s kitchens today, I notice subtle shifts: fewer indigenous varieties are passed down, revealing a silent erosion of cultural and ecological heritage.

In Indian mythology, two metaphors explain the origin of life: the womb (yoni) and the seed (bija). The fruit (phala) carries the seed, which begins the cycle again—a never-ending loop of life. But this cycle survives only through care. It is the community—farmers, elders, seed keepers, and children—who protect it, alongside quiet allies like bees, microbes, wind, and rain.

According to the UN FAO, 75% of plant genetic diversity has been lost since the early 20th century, as industrial seed systems replace local varieties. Experts like Dr. Vandana Shiva and Dr. Prabhakar Rao have long warned against this monoculture, emphasizing the urgency of protecting biodiversity and seed sovereignty.

Baharwa Lakhansen, a small village in Bihar, 29 km from Motihari, played a pivotal role in Gandhi’s Champaran Satyagraha. Today, it is witnessing a different struggle—the disappearance of farmer-saved seeds under the growing dominance of corporations like Monsanto. This loss threatens not just biodiversity, but also the traditional knowledge, rituals, and language embedded in these seeds.

Yet resistance endures. Every February and March, the village hosts Beej Daan, a seed-sharing fair where women farmers from neighboring villages exchange indigenous seeds—preserving biodiversity and tradition through collective action. The site becomes an embodiment of identity, celebration, and resistance, and the architectural intervention plays a vital role in giving it the recognition it deserves.

The design investigates how a place is shaped by collective memory—how architecture becomes activism, dispersing the act of saving and sharing throughout India. Using the Nolli map as a tool, the design begins with an understanding of the rural fabric—the relationship between built and unbuilt. Key pause points and natural site markers like the Peepal tree and Gandhi Smarak establish a spatial axis connecting memory, ecology, and community. Open spaces blend with the existing landscape, encouraging movement, pause, and interaction, while extending towards the fields yet retaining a central connection to the Peepal tree.

The project explores the interplay of solid and void through courtyards, plinths, and terraces, drawing from the rhythms of local architecture. Terraces function as essential social and working spaces—used for drying seeds, winnowing, and communal gathering. A play of levels creates visual and physical connections, encouraging movement and interaction. The central courtyard serves as a vibrant gathering space, hosting celebrations and fostering community interaction showing the adaptability of the spaces. The use of varied height plinth creates a playful environment, double height space with bamboo piers holds the works of the women.

The seed bank, envisioned as a temple, unfolds along a pradakshina path around the sacred Peepal tree —symbolizing the continuity of life. Merging into the landscape via a seasonal trail, the underground seed bank uses natural cooling to extend seed longevity. Edge conditions serve as vital thresholds, revealing human-ecosystem relationships. The lake edge, for example, transforms into a vibrant market space-becoming a key site of interaction.

Passive strategies—green roofs, stack effect, evaporative cooling, and locally sourced materials—anchor the project in sustainability. Bricks salvaged from an old brick kiln on site carry material memory and reduce embodied energy. The khatiya, a familiar wooden bed woven with jute or cotton fiber, is adapted into partition walls that can transform into sleeping surfaces—rooting the architecture in local practice.

A study of indigenous seed preservation revealed deeply communal, low-tech methods: matkas (terracotta pots), neem treatment, ash coating, bamboo containers sealed with mud and cow dung. Terracotta flooring keeps interiors naturally cool, reinforcing a sustainable, context-sensitive design approach. Spaces are woven out of pavilions, courtyards, talabs, and gardens—stitched together through corridors and shadows. Architecture, here, does not dominate the land but becomes it extending the topography rather than altering it.

Beej becomes a living archive—a space of expression, livelihood, and memory. It bridges the cycles of nature and human connection, celebrating not only seeds but also culture, diversity, and ecology. As such, it acts not only as a regional intervention but as a global call for action—a force of nature in itself.