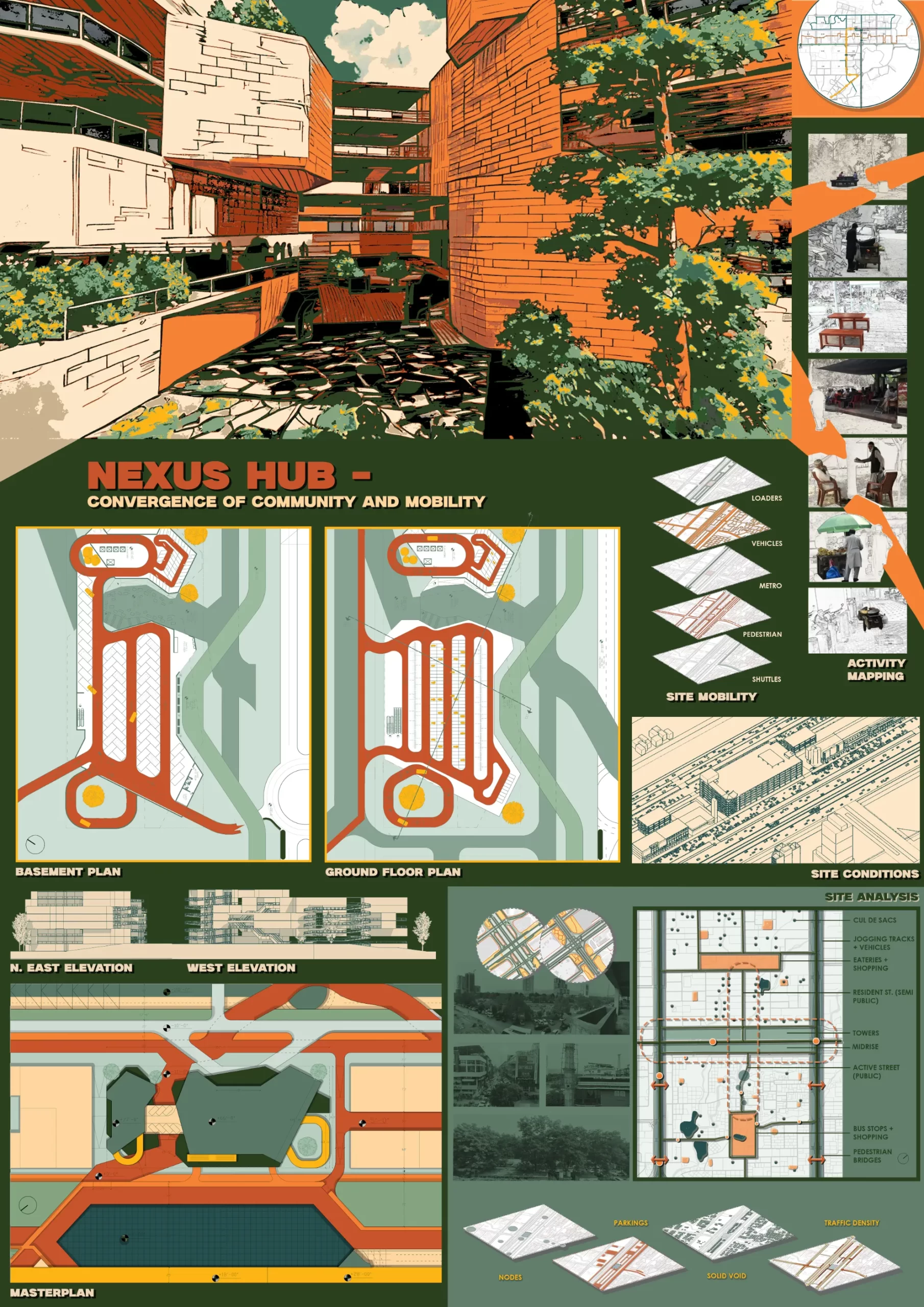

The Nexus Hub // Convergence of Community and Mobility - Vertical Restructuring of Flows

The extreme effects of global urbanization, growing populations, and environmental degradation are continuously increasing in cities today, leading to a state of crisis. While cars are dominating roads, public life is shrinking and being pushed to the side. Environmental stress and isolation are no longer theoretical, but experienced daily where streets serve vehicles instead of people. The Nexus Hub addresses these challenges as a multimodal transit facility that reclaims public space, bridges social divides, and envisions a resilient urban future based on local realities, yet shaped by global aspirations.

Cities are predicted to accommodate over five billion people by 2030, urging the need for creation of spaces that sustain the booming population without worsening already existing divides. The Blue Area of Islamabad is concerned with these emerging dilemmas, where expansive road surfaces separate communities, retain heat, and become obstacles for the underprivileged, requiring revision through a deep understanding of community needs.

Islamabad isn’t just a city that grew with time, but was drawn, imagined, and constructed as a modernist dynapolis. The lack of a traditional city center makes the commercial and business spine, the Blue Area, act as a convergence point. However, as the city evolved, the disparities also grew. The rigid functional zoning reinforced socio-economic divides, where the elite were housed in the planned residential quarters, and the workers who sustained the city’s daily life, such as the sanitation staff, street vendors, and domestic workers, were excluded from the formal plan, settling in informal colonies within the city’s gaps. Blue Area eventually began acting as a physical barrier between privilege and informality.

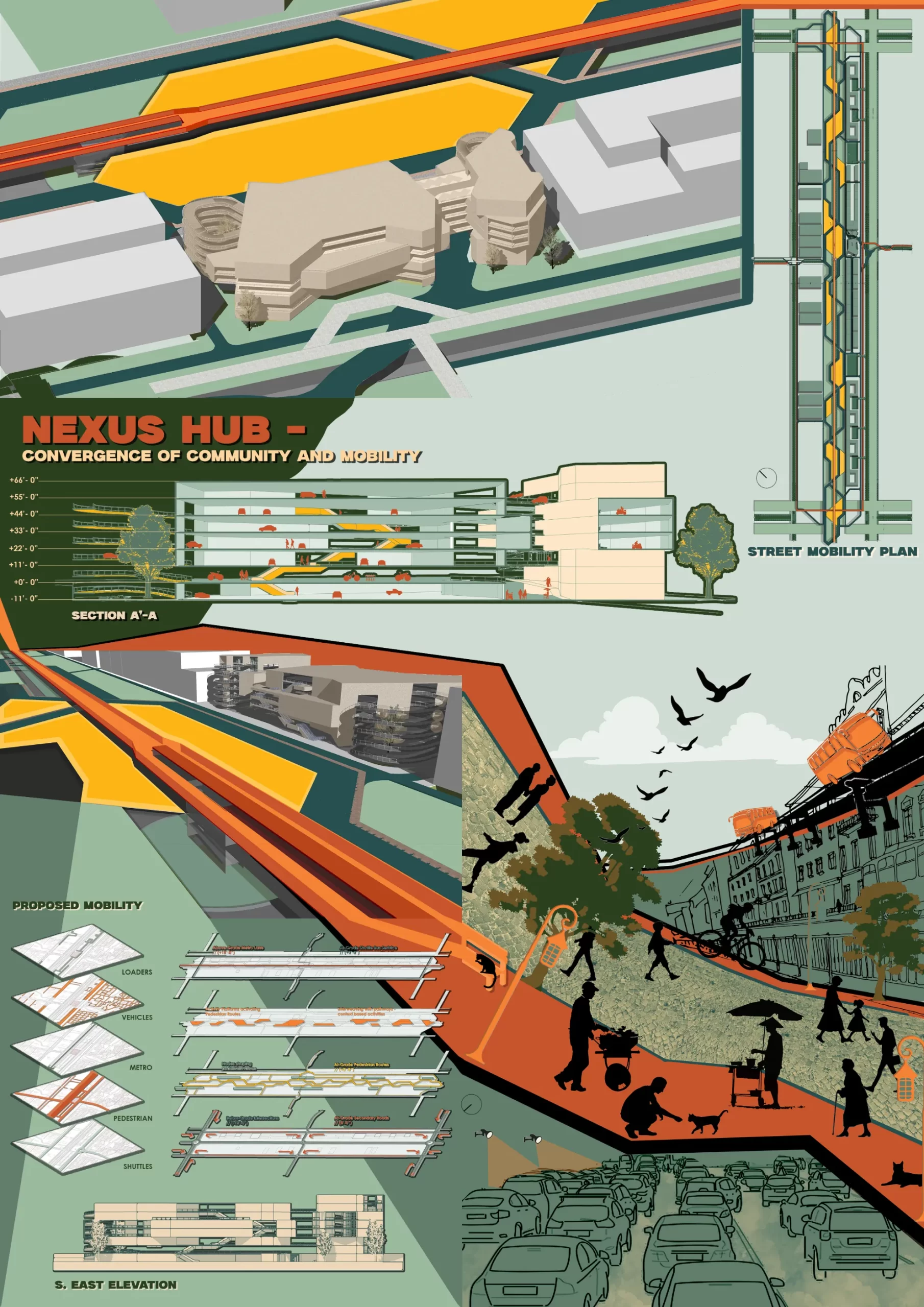

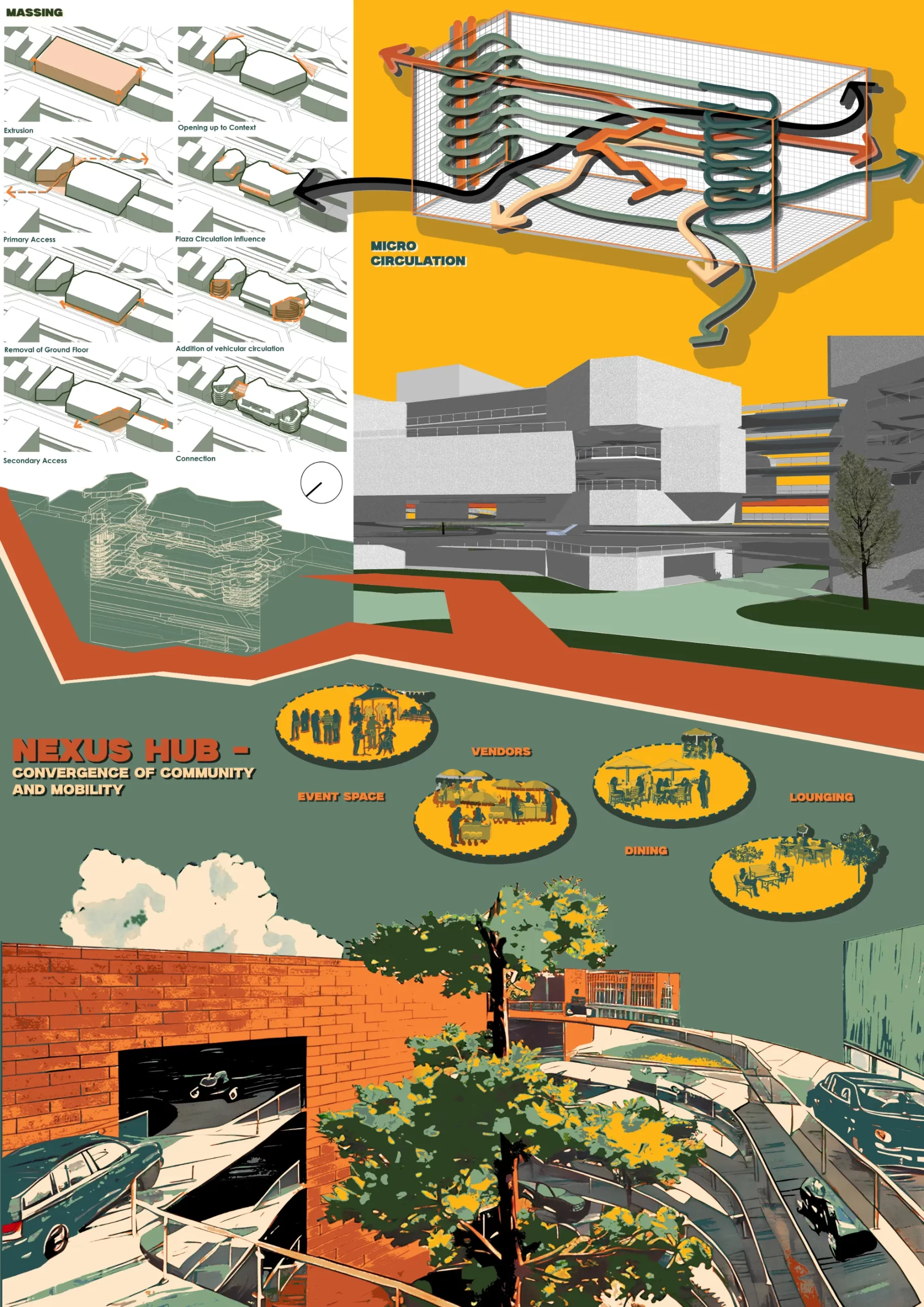

The Nexus Hub instead suggests a shift in narrative where the street is returned to pedestrians by pushing vehicles underground and elevating public transit above ground. This reconfigured mobility network reclaims valuable space, allowing people to interact and thrive.

The macro-level intervention layers the current road infrastructure into a stacked mobility network. Uninterrupted traffic flow is established and surface-level congestion is reduced, allowing for a pedestrian corridor with designated activity platforms, based on contextual needs. Parking, often a dead zone, now acts as a major seam linking both sides of the site by limiting vehicles to a structured, smart, and time-based parking system. These interventions not only reduce the reliance on cars but also transform this infrastructure into a tool of inclusion and sustainability by integrating users' lifestyles into the urban environment.

The micro-level design of the building focuses on one significant spatial gesture: the crack. It splits the building to allow natural pedestrian flow, creating permeability in the rigid plan of Islamabad. Vertical circulation is made transparent and engaging, promoting intuitive way-finding and layered engagement. The ground floor is removed to allow cyclists and pedestrians to filter through, whereas the cars are tucked away on the upper levels. The form of the building reflects the surrounding mobility patterns by responding to user flows within and around the site.

From a social lens, the hub links diverse user backgrounds and acts as the converging point of the city by creating dignified and designated spaces for the informal vendors. The office workers and visitors can engage with these vendors in shared environments, contributing to economic exchange and social conversation. These increased levels of activity result in safe and vibrant atmospheres. The previously disjointed experience of walking is replaced by a new urban phenomenon, where the dialogue between 'formal' and 'informal' is treated as an important aspect of the vibrancy of city life.

From an environmental lens, the hub reduces the Urban Heat Island effect by replacing the extensive road surfaces with grassy patches, rain gardens, and permeable pavers. The shaded social crack and the tree-lined walkways help cool the pedestrian realm, while green terraces integrated within the parking create microclimates and reduce runoff. The hub not only reduces the environmental stress, but also revisits the idea of a ‘Green Islamabad’, which has been lost in the vehicular-centric policies and developments made.

From an urban lens, the hub provides a scalable and adaptable model, where the layered approach to mobility is applicable in any car-dominant urban zone. It aligns with the common global goals aiming for emission reduction, enhanced livability of cities, and reduced social disparities. At the same time, it’s still deeply rooted in Islamabad’s cultural, spatial, and economic dynamics, contextualizing the design solution to the unique, multicultural aspects of the city.

The Nexus Hub ultimately responds to the emerging challenges of urban cities, where those once excluded now walk in the same spaces, with the same dignity, and with the same sense of belonging, a crucial step in the efforts to reclaim streets and reduce the urban divide.

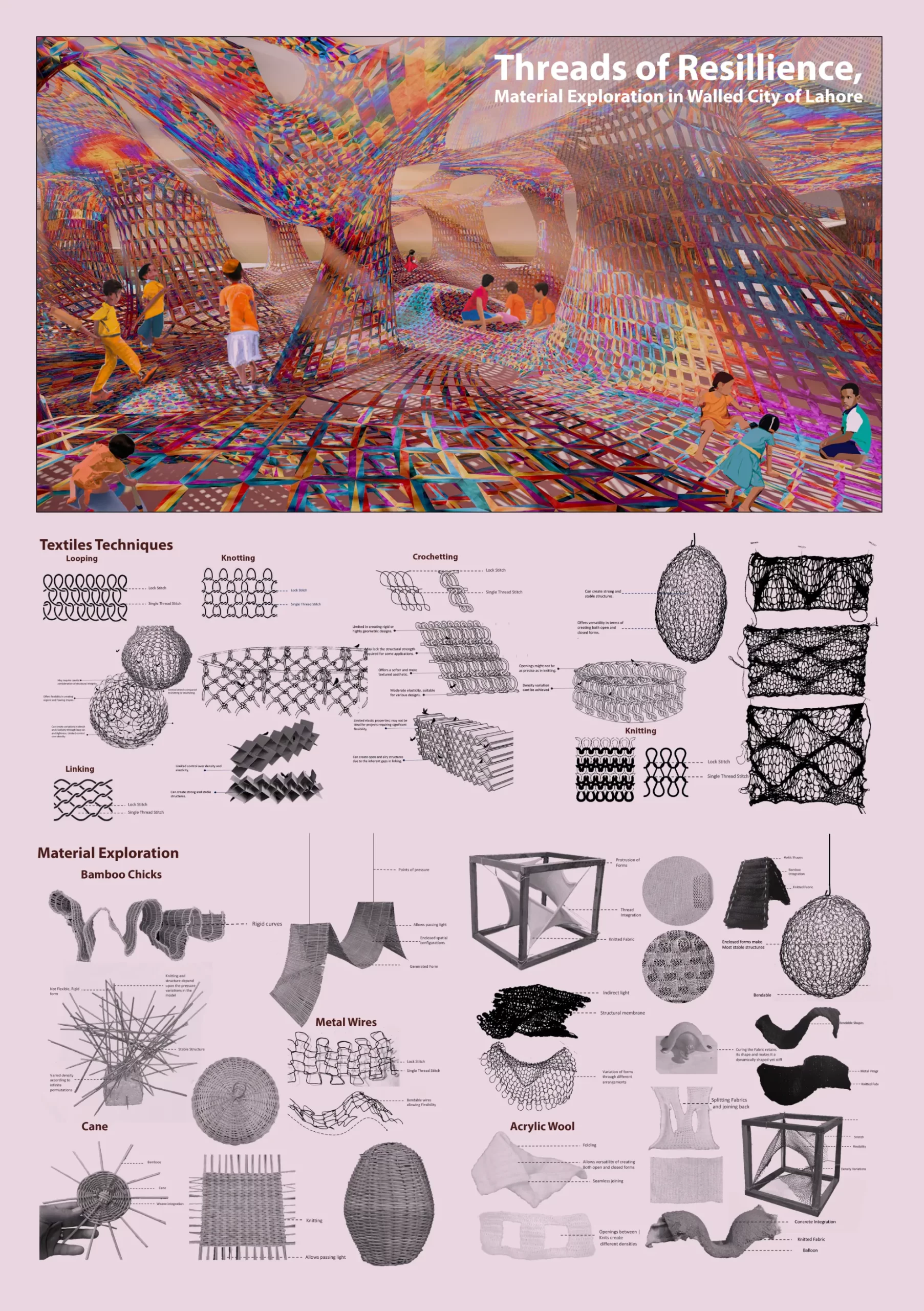

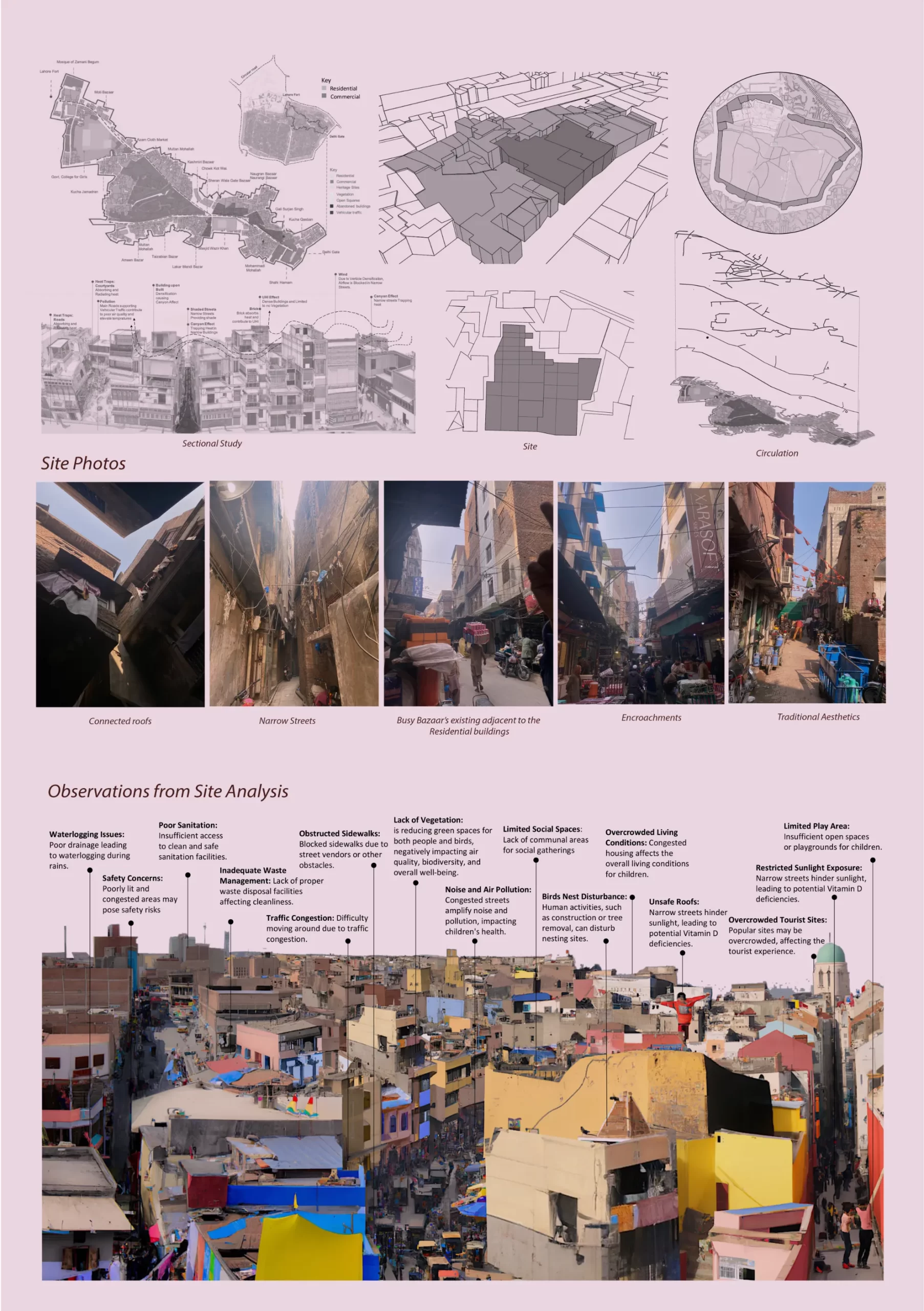

‘Threads of Resilience: Material Explorations in Rooftop Connectivity, Delhi Gate, Walled city of Lahore.’

The walled city of Lahore is one of the oldest and densest settlements in Lahore, renowned for its rich heritage of art, architecture and culture dating back to the Mughal Era, this project explores the intersection of traditional textile techniques, innovative architectural design, and sustainable material use to create vibrant and functional spaces for children in the historic locality. The aim is to address the challenges posed by the dense urban fabric and enhance the quality of life for its youngest inhabitants.

The Walled City is characterized by narrow, winding passageways and towering mixed-use buildings, creating a dark and confined environment. This urban density restricts natural light, airflow, and open spaces for children to play, contributing to a significant vitamin D deficiency among the youth. The main stakeholders for this project are the children of the Walled City, who need safe, accessible, and engaging spaces for recreation and social interaction.

The foundation of this project lies in understanding the historical and cultural significance of textiles in the Walled City. Textiles have been an integral part of the city's artistic and architectural heritage, influencing various forms of expression and construction. By studying this rich history, the project seeks to draw parallels between traditional textile techniques and contemporary architectural practices.

The research journey spanned theoretical discussions on stitches and textile techniques to hands-on exploration of found materials on the site. The goal was to synthesize sustainable and contextually responsive architectural solutions, considering the ecological impact of materials, waste management strategies, and the cultural context of the Walled City. This approach ensured a holistic and informed design process.

Conceptually, the project is rooted in the seamless integration of traditional textile techniques, especially knitting, with architectural materiality. The concept extends beyond theoretical discussions, manifesting in the tangible utilization of found objects and scrap materials. Acrylic wool, bendable metal wires, cane, and bamboo chicks are not just elements; they are integral components of an innovative architectural language that challenges conventional notions of construction. This project transforms knitting into a robust and versatile architectural technique.

The design creatively utilizes knitted elements to allow indirect light, reinterpreting the urban fabric with sensitivity to the local context. Design sensitivity is inherent in the project's response to the practical needs of the community. Materials like acrylic wool are chosen not just for their visual appeal but for their ability to create a safe and vibrant space for children to play. Beyond aesthetics, design sensitivity embraces functionality, contributing to the fundamental well-being of the inhabitants within the constraints of the urban environment.

Sustainability is not merely a goal but a commitment evident in the project's use of found and repurposed materials. The reduced carbon footprint is a result of sourcing materials locally and repurposing elements that might have otherwise been discarded. Concrete application is thoughtfully limited, minimizing environmental impact and advocating for sustainable design thinking within the urban context.

Placemaking becomes a pivotal aspect of the project, responding to the spatial constraints of the Walled City. The design aims to create a place for social interaction and play, recognizing the deficiency of recreational spaces, especially for children. The meticulous consideration of indirect light and waterproofing ensures that the space is not only functional but also conducive to positive interactions, making it a beacon for placemaking within the historical and cultural context of Lahore echoing a vision where adaptability, sustainability, and community thrive in unison.

The project redefines spatial appreciation and visual impacts, recognizing the need for adaptable and sustainable solutions. By embracing knitting as a construction technique and experimenting with unconventional materials, the project sets a precedent for future-proof designs prioritizing innovation, sustainability, and community well-being.

In Conclusion, this project intertwines tradition and innovation, offering a sustainable beacon for the future. As acrylic wool and bendable metal wires knit a resilient narrative, the design stands not only as a structure but as a testament to the transformative potential of thoughtful architecture by addressing the unique challenges of the Walled City, it creates a vibrant and functional space that not only celebrates the rich cultural heritage of Lahore but fosters a sense of belonging and improves the quality of life for its youngest residents.

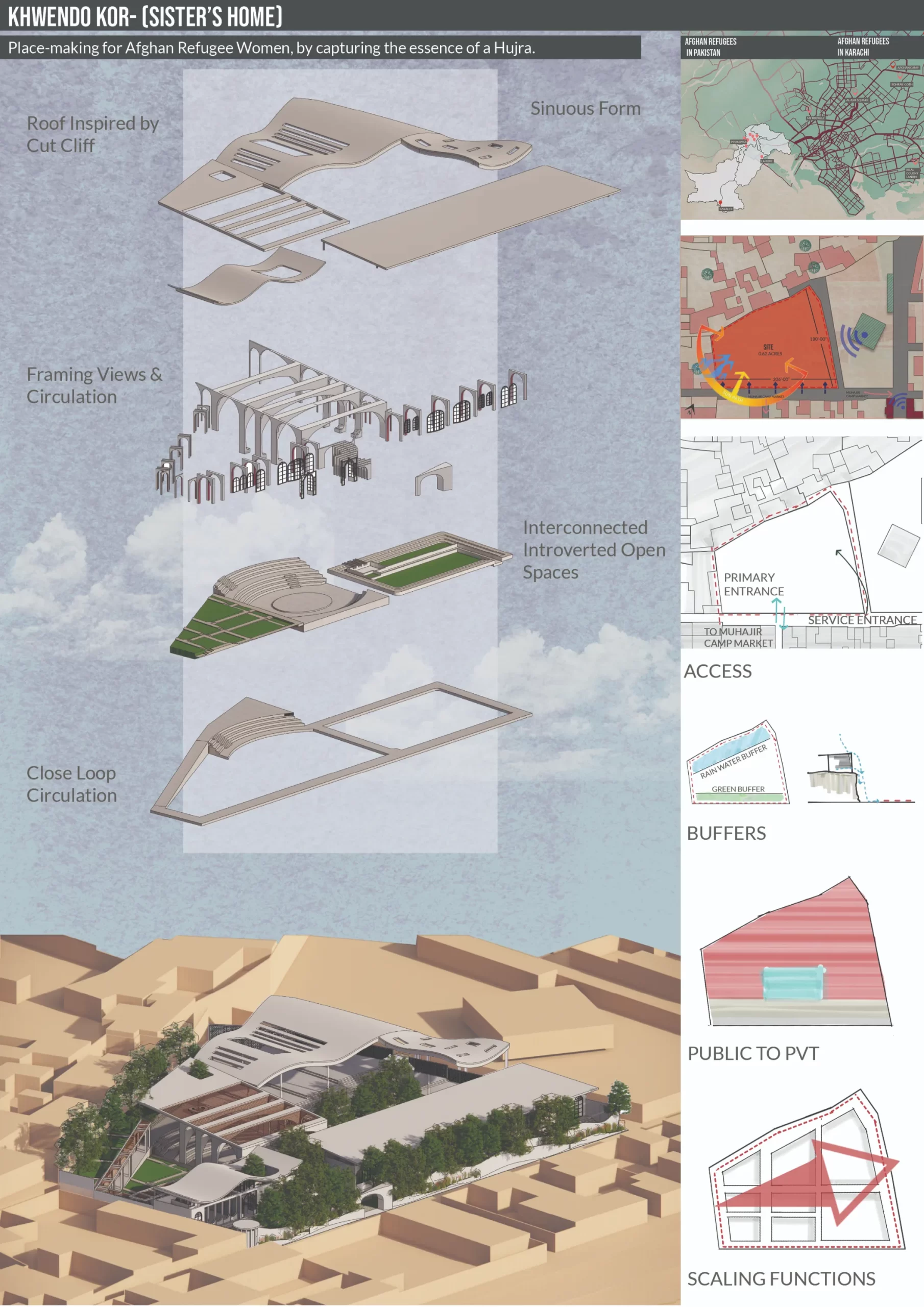

Sister’s Home

Place-making through creation of an opportunity and learning centre for Afghan refugee women in Karachi, by capturing the essence of a “Hujra”.

A refugee lives through 2 wars, one that is going on in their homeland, and the other that is waged against them at their host country where they are labelled as “others”. Away from their “legal-homeland”, their inter-community bonds are broken, power dynamics and social hierarchies are further amplified; leading them to question their own role in the society, they feel placeless.

After 43 years of Pakistan hosting Afghan refugees, the refugee camps have transformed into informal settlements, with their own ecosystems. In Karachi’s Afghan Basti, the ungoverned eco-systems strongly govern, and control the lives, movement and opportunities of women in the basti. They have no place to seek refuge in the entire refugee camp.

The project explores place-making through the creation of a “sister’s home”, a community centre for women, that helps reestablish broken inter-community bonds. It helps validate their citizenship and right to living and personal growth, as it’s a permanent structure made exclusively for them, in an “impermanent camp”. It aids in creating a sense of belonging, by understanding the phenomenology of Afghan spaces and culture. The process is participatory, and place-making is achieved through creation of multi-purpose and multi-functional communal spaces.

Simultaneously it gives them agency to reshape their lives as it will provide spatial and financial agency. This was done keeping in mind the language of space, how the spatial order, proximity, organisation all dictate the relationship between the people occupying it, as well as the relationship between the space itself and places surrounding it.

PUSHING THE RESET BUTTON:

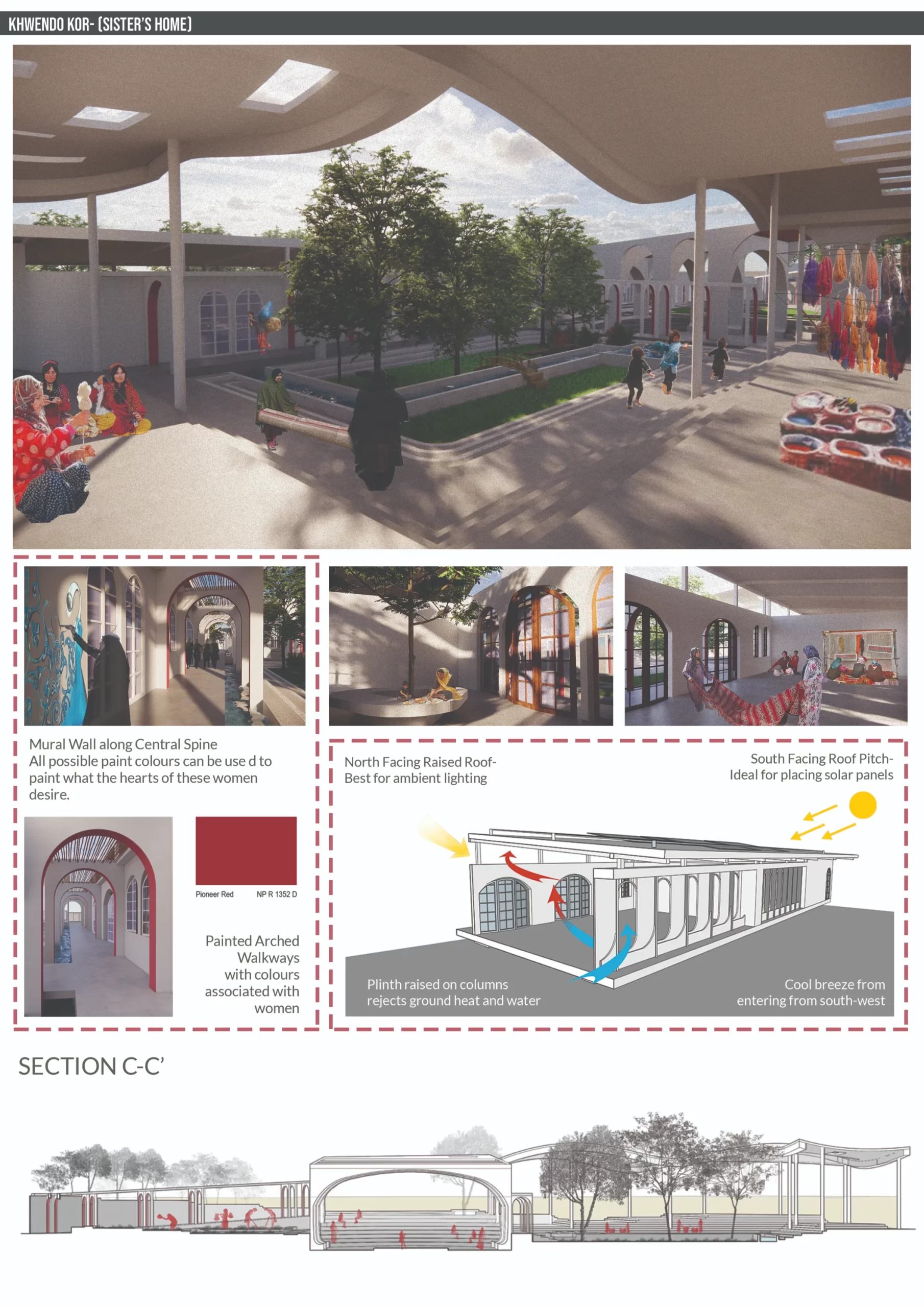

The “Sister’s Home” is a place by the women for the women. A sense of belonging is created as the space becomes a rostrum for creation of ‘tangible cultural heritage’ and ‘intangible cultural connections’, through a series of interconnected courts and pavilions.

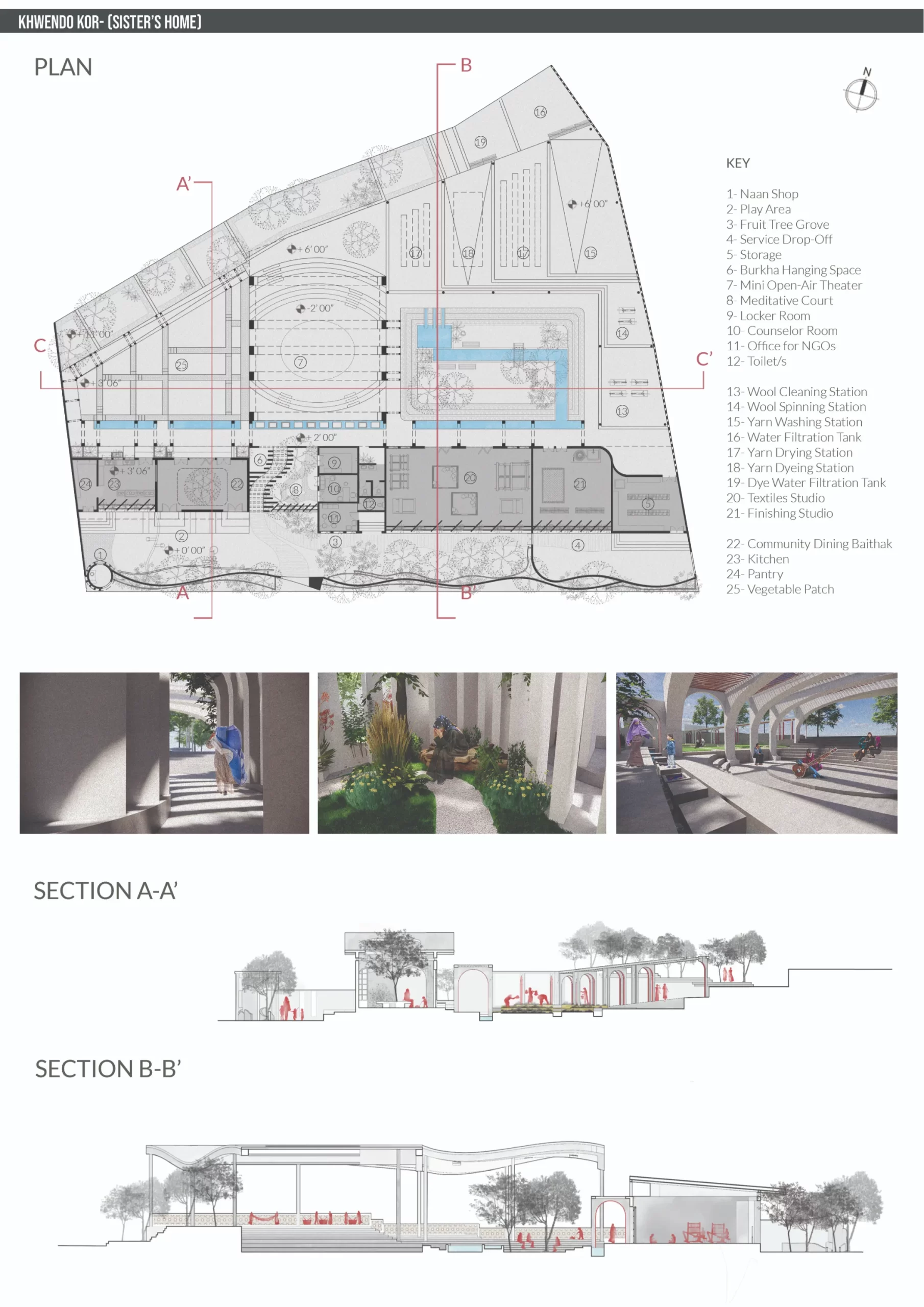

Economical Reset-

Although a flexible space, the main program of the project is an Afghan carpet-making and traditional Afghan embroidering facility, and a community kitchen. The former is providing employment for the women in the basti. While the latter is supplemented with a vegetable garden and fruit tree grove so that a self-sustaining soup kitchen is created for the women of the basti.

Social Reset-

The project explores the source of its user’s melancholy, and becomes a place that makes them feel like they “belong”. The architecture itself becomes a vessel for healing as its invites women from across the basti to share their woes, it becomes an arena for story-telling. Simultaneously it acts as a physical refuge to sit amongst nature by yourself or in a group to work towards a better self. Besides that, the program entails a counselling room that can help resolve one’s own personal issues or issues amongst groups, through professional help.

Environmental Reset-

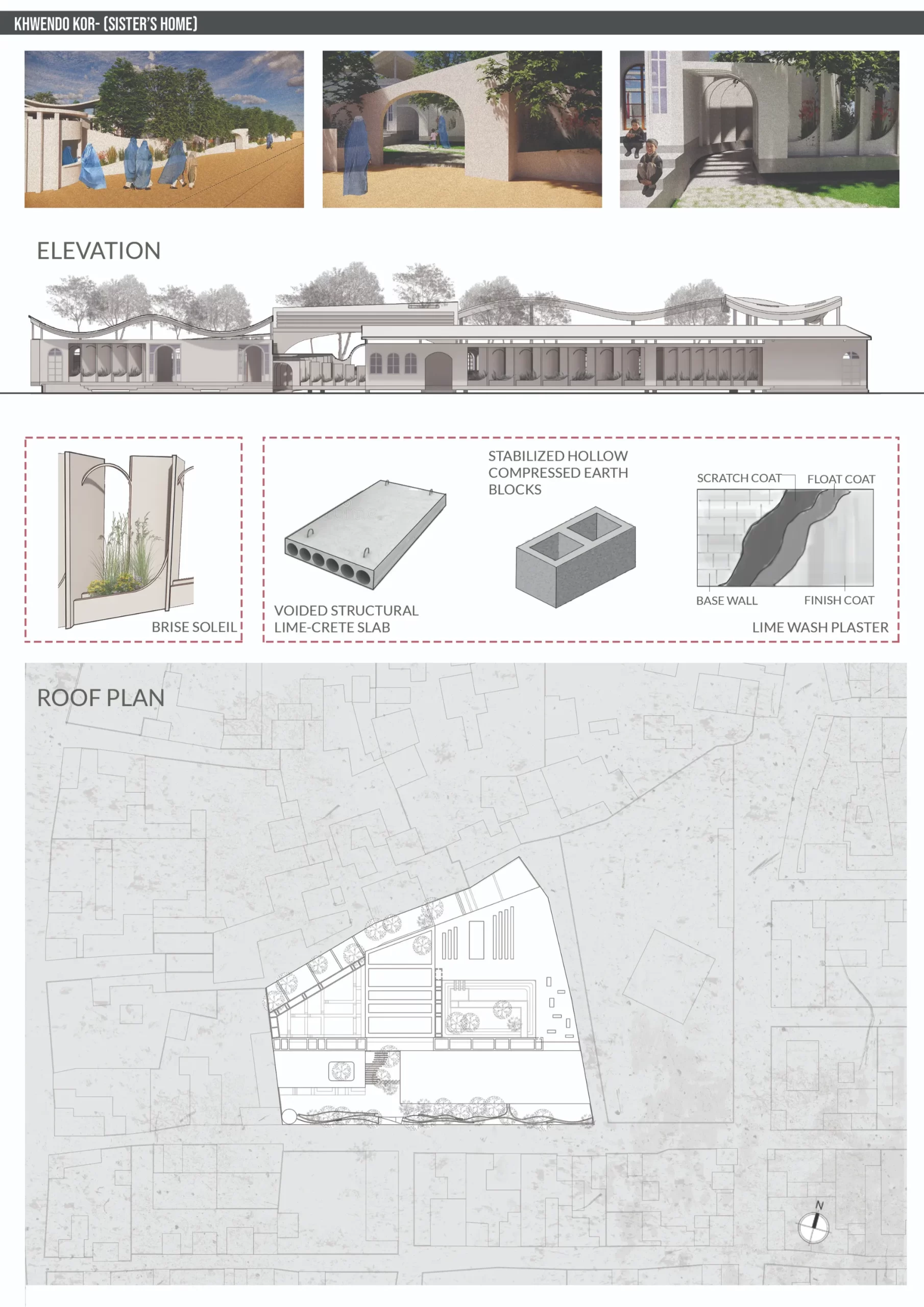

In the densely built Aghan Basti void of vegetation, the project emerges as a green oasis; with 75% of the plot unbuilt, while 65% is green spaces. Structurally the architecture steers away from the harsh lines and geometry of the basti, incorporating more sinuous forms that is not only a reminder of geographies that once existed, but also announces itself to be a space that is feminine. Femininity is also seen through use of integration of colours typically associated with women. Besides that, the materiality of the space is one to last, unlike the impermanent mud construction seen across the basti. However, the planning of the space takes cues from existing Afghan architectural typologies, of residences and Hujras.

Cultural Reset-

A Hujra is a place in Afghani culture reserved for its men, it acts as a parliament, a meeting and gathering space, a place to learn, create and earn, a place to get entertained and share joys and sorrows. However, women do not have such space in Afghan culture. It was noted that the streets have become a modern day hujra, however since the women can’t overtake the streets, the project then becomes one for them. A primary physical street running across the programs of the project, and the closed loop circulation increases the chance encounters and provides fleeting glances to build familiarity with one another to help strengthen the sense of community. The apertures and colonnades in the project frame the movement and moments, as mode of story-telling; that materialises itself as conversations during carpet weaving or cooking then sharing a meal at the soup kitchen or while entertaining at the mini theatre. The theatre also doubles as a place to teach and learn transforming into a classroom. And when days’ work is over, the entire scheme can metamorphose into gathering space for festivities like Eid, Nowroz, weddings, etc. once again bringing the women together.