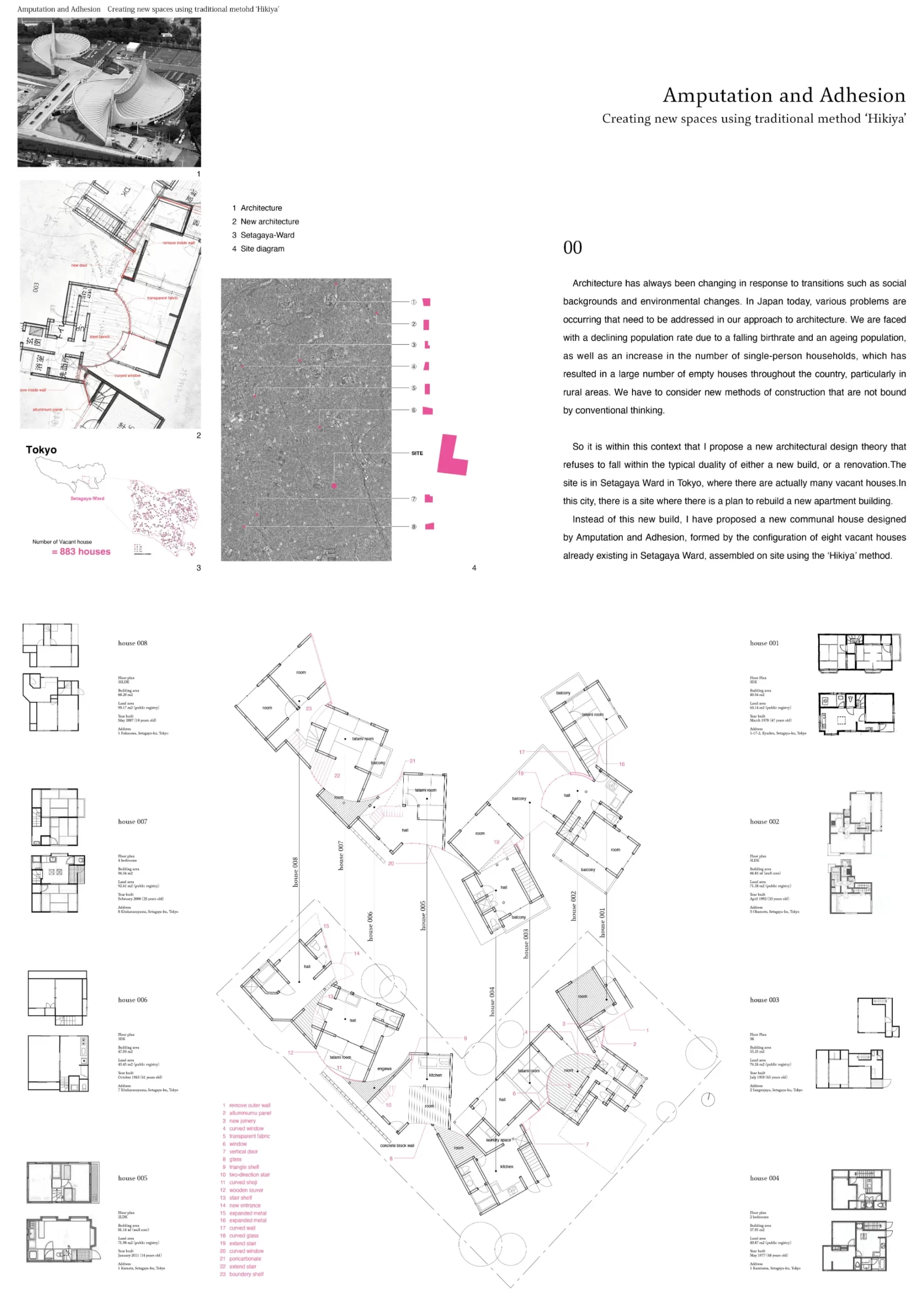

Amputation and Adhesion ~Creating new spaces using the traditional construction method 'Hikiya' ~

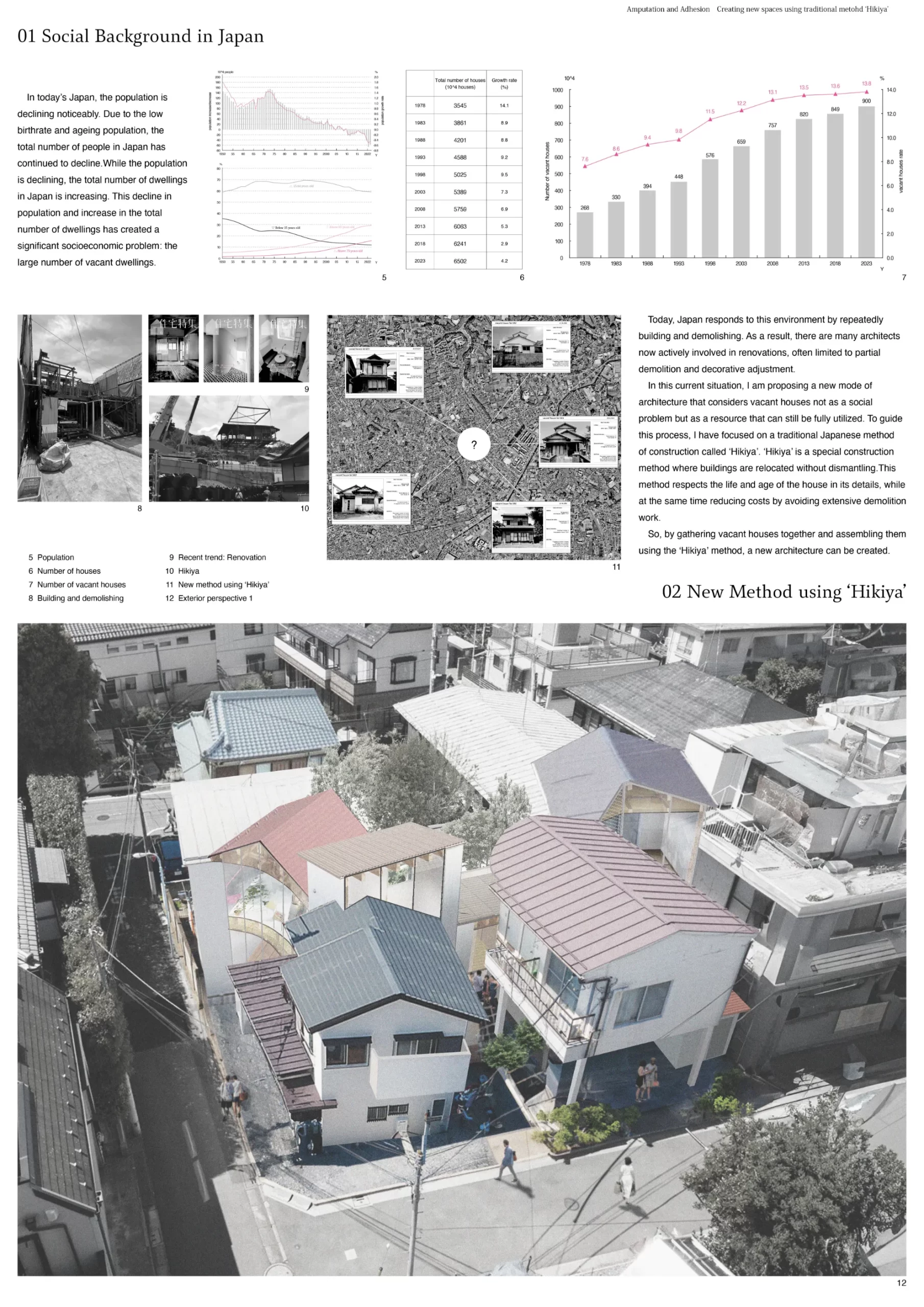

Architecture has always been changing in response to transitions such as social backgrounds and environmental changes. In Japan today, various problems are occurring that need to be addressed in our approach to architecture. We are faced with a declining population rate due to a falling birthrate and an ageing population, as well as an increase in the number of single-person households, which has resulted in a large number of empty houses throughout the country, particularly in rural areas. We have to consider new methods of construction that are not bound by conventional thinking.

So it is within this context that I propose a new architectural design theory that refuses to fall within the typical duality of either a new build, or a renovation.

First of all, I will explain the current situation in Japan. In today's Japan, the population is declining noticeably. Due to the low birthrate and ageing population, the total number of people in Japan has continued to decline over the past seven years alone, with a decrease of more than two million people. While the population is declining, the total number of dwellings in Japan is increasing. This decline in population and increase in the total number of dwellings has created a significant socioeconomic problem: the large number of vacant dwellings scattered throughout the country.

Today, Japan responds to this environment by repeatedly building and demolishing. This culture of crash and build is predominantly controlled by economic pressures to build new, and by the issue of inheritance tax that makes it more viable to demolish and build again. As a result, there are many architects now actively involved in renovations, which has created a recent trend of conservative, somewhat superficial renovations, often limited to partial demolition and decorative adjustment. In this current situation, I am proposing a new mode of architecture that considers vacant houses not as a social problem but as a resource that can still be fully utilized. To guide this process, I have focused on a traditional Japanese method of construction called 'Hikiya'. 'Hikiya' is a special construction method where buildings are relocated without dismantling. Only the foundations and external walls are removed as required, and the structure is moved as it is. This method respects the life and age of the house in its details, while at the same time reducing costs by avoiding extensive demolition work. By retaining the structure and framework of these buildings, it is also a form of cultural preservation, by continuing the life of the craftsmanship inherent in Japanese building culture. So, by gathering vacant houses together and assembling them using the ʻHikiyaʼ method, a new architecture can be created.

The 'Amputation and Adhesion' method is proposed as a design method for assembling vacant houses. Defects are often considered negative 'drawbacks' due to the cost of repair and partial demolition, but here such defects are seen as a positive resource, and cut out to be retained in various ways. Specifically, this method involves cutting out the missing or ‘sick’ parts of a vacant house, and then gluing the cut surfaces of another house together to complement each other in new spatial arrangements. I came up with a variety of patterns on the plan, such as a straightforward pattern that follows the grid of the house, a pattern with a diagonal penetration that dares to betray the existing structure, or a pattern in which curves are inserted as a completely different language. Through the combination of these patterns and new configurations, a new spatial experience is formed that creates a sense of mystery and delight to the people who live there.

After the initial reconfiguration, furniture and new materials called bond elements are inserted as tools to solve the discrepancies that occur at the moment of joining. These could take the form of a mysterious staircase that connects different storey heights, or a transparent fabric used for a new type of partition, or a built-in shelf as a new way to form a boundary. The accumulation of these disparate elements and unique configurations bond together architecturally, which is at once symbolic of this new method of architectural preservation.

In reality, I will now talk you through a case study that I developed using this method. The site is in Setagaya Ward in Tokyo, where there are actually many vacant houses. In this city, there is a site where there is a plan to rebuild a new apartment building. Instead of this new build, I have proposed a new communal house designed by Amputation and Adhesion, formed by the configuration of eight vacant houses already existing in Setagaya Ward, assembled on site using the hikiya method. This is the floor plan. Let me explain the configuration

It has the overall appearance of a narrow residential area in Japan, but at the same time has a new face. The exterior exposes the section of the vacant house as it is in place. This creates a shocking façade that was not present in the existing elevation. Furthermore, the sections, which are both amputation and adhesion, lead the visitor to ponder the invisible after images, such as the contours of what should have once been or the life that was lived there. While the house has a variety of visual attractions through its clear-cut methods, it also has another curious attraction that leads us into the world of the invisible, the world of the imaginary. This is the spatialization of my new architecture method, that critically addresses the socioeconomic issues we are currently faced with in Japan, while also realizing a new spatial experience, that is more attune with the current times.

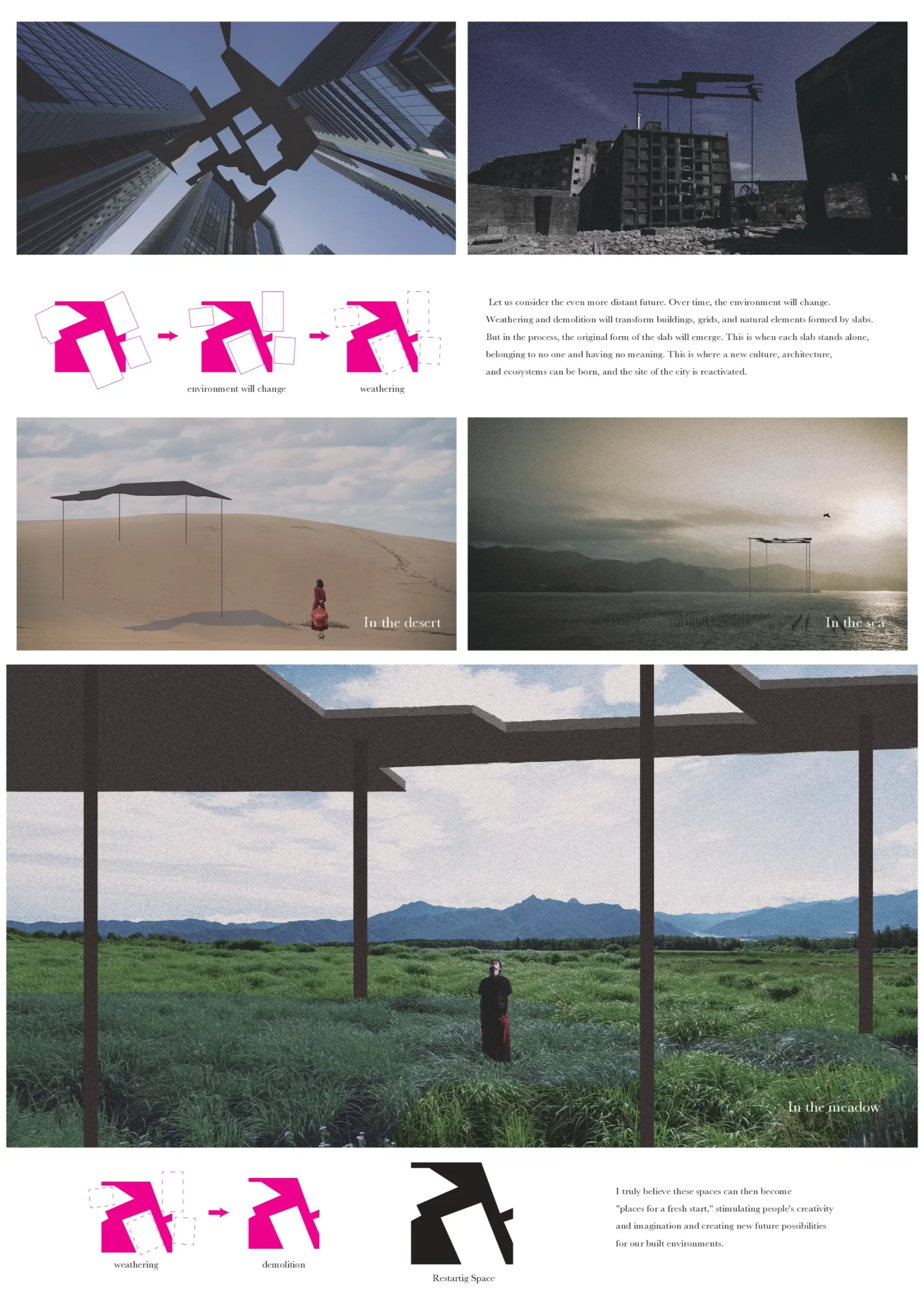

Restarting Space

Our cities are currently shaped by a controlling system that limits our potential, controls our behaviour, separates people, and distances us from nature. However, instead of giving up on the system, we should strive to develop a symbiotic relationship with our built environment to move forward and imagine a new future. To achieve this, we must accept the status quo but also critically examine our cities.

By looking at the gaps in our cities, we can discover new possibilities. While our cities today exhibit division and separation in buildings, communities, and relationships, there is potential for positive change by creatively exploring these gaps. Nature can flourish, personal exploration can thrive, and new urban development opportunities can arise. In order to tap into this potential, we need a framework for creating a system that is neutral, without ownership or authority, and capable of nurturing future possibilities.

One possible framework is the reinterpretation of the grid. By overlaying a rectilinear grid over the city, the overlaps of the gap spaces within the built environment can reveal a new form. This form would emerge by chance, originating from the rational grid's overlap with the lived realities of the gaps. It would transcend human design, resembling something closer to the wild—a form that is anti-urban in its organisation and organic in its origin from the conditions of the gap spaces.

Another source of inspiration for this proposal is the idea of a monolith. The overlapping of the grid and gap spaces gives rise to an organic form that can be best expressed as a monolith—a slab-like architectural element. To achieve sustainability, the slab is constructed using concrete reinforced with carbon nanotubes, a lightweight material that is approximately 20 times stronger than steel. The monochromatic black colour of the carbon signifies its lack of ownership.

Three different patterns have been developed based on the elevation of the grid, the size of the mass, and the objects to be hollowed out. The "field" pattern connects several buildings to create a positive community space, such as a plaza or park. The "branch" pattern emerges from the complex connection of alleyways, fostering random encounters and exploration. The "archipelago" pattern consists of multiple small places that reflect the relationships between neighbours, allowing for individuality, diversity, and creativity to flourish.

These slabs offer solutions to various problems, both large and small. On a personal level, they can extend the usability of balconies or patios, providing larger floor areas for activities and gatherings. From a broader social perspective, the slab system can address urban challenges in disaster-prone regions like Asia. The carbon nanotube structure of the slabs enables them to withstand floods and earthquakes, serving as evacuation spaces and shelters during disasters. Additionally, the slabs can contribute to sustainability by incorporating transparent thin-film solar cells into their design, generating renewable energy and supplying it to the surrounding buildings and community.

By filling the slabs with soil and planting trees and plants, the gaps between cities can be transformed into green spaces, allowing for the coexistence of urban areas and vegetation. Over time, as buildings, grids, and natural elements weather and undergo demolition, the original form of the slab will emerge, standing alone and belonging to no one. This creates an opportunity for new cultures, architectures, and ecosystems to be born, reactivating the site of the city.

These spaces can become "places for a fresh start," stimulating people's creativity and imagination and creating new possibilities for our built environments.