a room for “weaving” our life

In modern Japan, despite high literacy rates, many people remain invisible and voiceless. Elderly individuals, non-regular workers, single parents, immigrants, LGBTQ+ persons, and people with disabilities are often marginalized—not only economically or institutionally, but spatially and emotionally. Their lives are fragmented by labor and caregiving, leaving them with little time, space, or community in which to reflect or be heard.

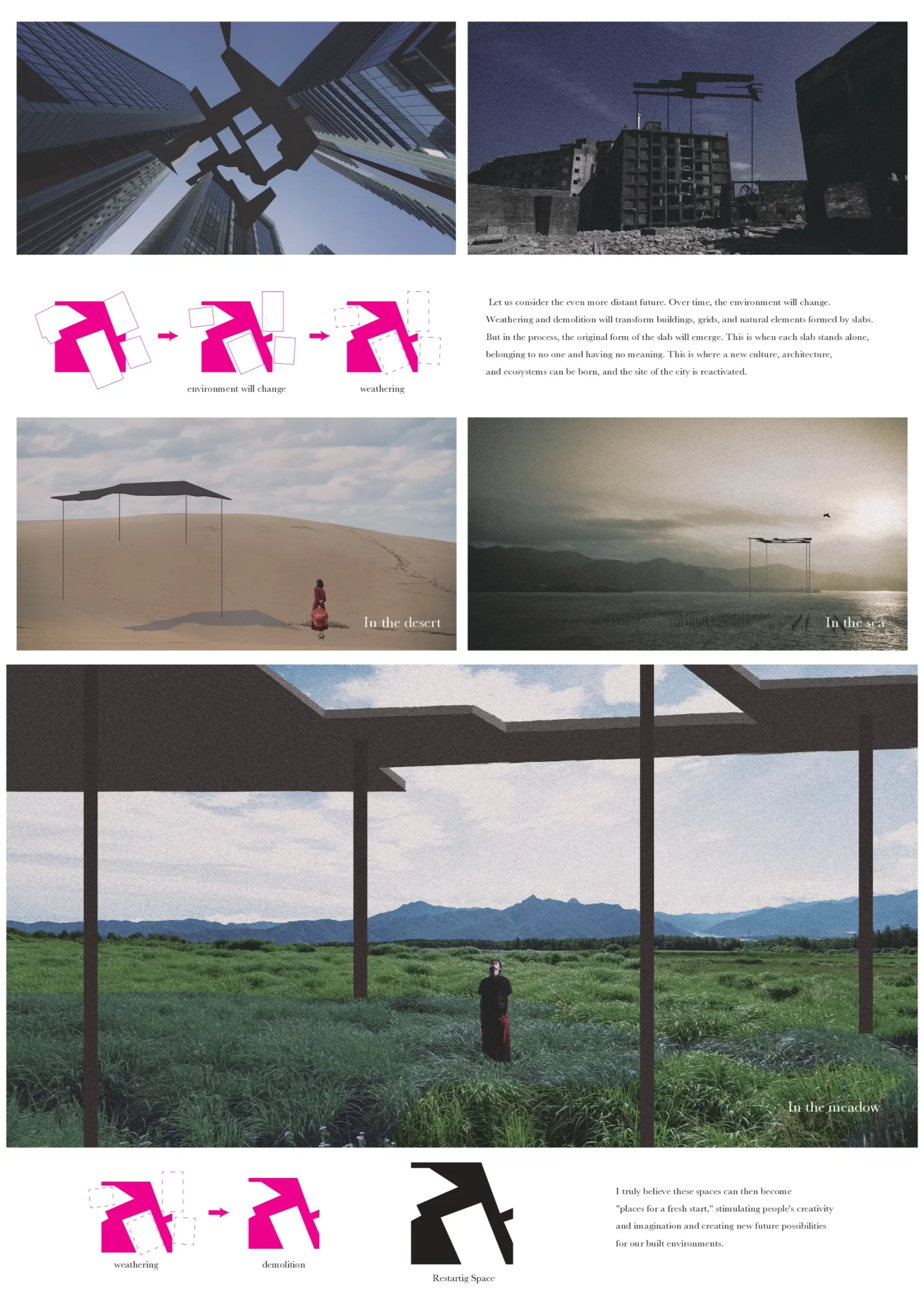

This project proposes an interior—a soft architecture—for people who are usually excluded from the architectural imagination. It is a space not built by professionals for passive users, but one that can be made by the people themselves, using simple tools and slow, repeated actions. The aim is to create a place where people can read, write, or simply sit in silence—a space for archiving ordinary lives.

The conceptual starting point is twofold: First, Virginia Woolf’s assertion in A Room of One’s Own that a woman needs “money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” Second, Kazuko Tsurumi’s “Life Writing Movement,” in which ordinary housewives gathered in postwar Japan to document their daily lives in their own words. These two visions—solitude and collectivity—are not contradictory, but complementary. To write is to reflect, but also to connect. The design seeks to spatialize both gestures.

The architectural form is inspired by a children’s knitting toy, used to make cord by looping yarn through a circular frame. Here, a similar technique is scaled up: yarn is woven between vertical poles and a wooden frame, gradually building up a tubular, fabric-like enclosure. This creates a space that is both inside and outside—a room with soft, stretchable walls. The woven threads define the boundary, but gently, allowing light, air, and sound to filter through. The outer frame provides a space for shared activity and connection; the woven interior creates a cocoon for solitude and contemplation.

The process of making this space is as important as the space itself. Like textile work, it is accumulative, repetitive, and low-barrier. It does not require technical expertise or financial power—only time, intention, and community. People can build their own “rooms” at their own pace, with their own colors and textures, according to the needs of their bodies and environments. In this way, the space remains flexible, portable, and personal.

Examples of use include:

This is not architecture as monument, but as memory. Not a structure that asserts permanence, but one that archives impermanence. The woven room becomes a living document—of labor, care, creativity, and connection.

Ultimately, architecture and interior design have the power not only to house people, but to reveal their presence. A closed room can be a sanctuary, but a woven room is a gesture: it says “I am here,” softly but clearly, in a world where many lives remain unheard. By offering a way to craft one's own space—and leave a trace of one's own life—it becomes a tool for quiet empowerment, and a collective act of remembering.

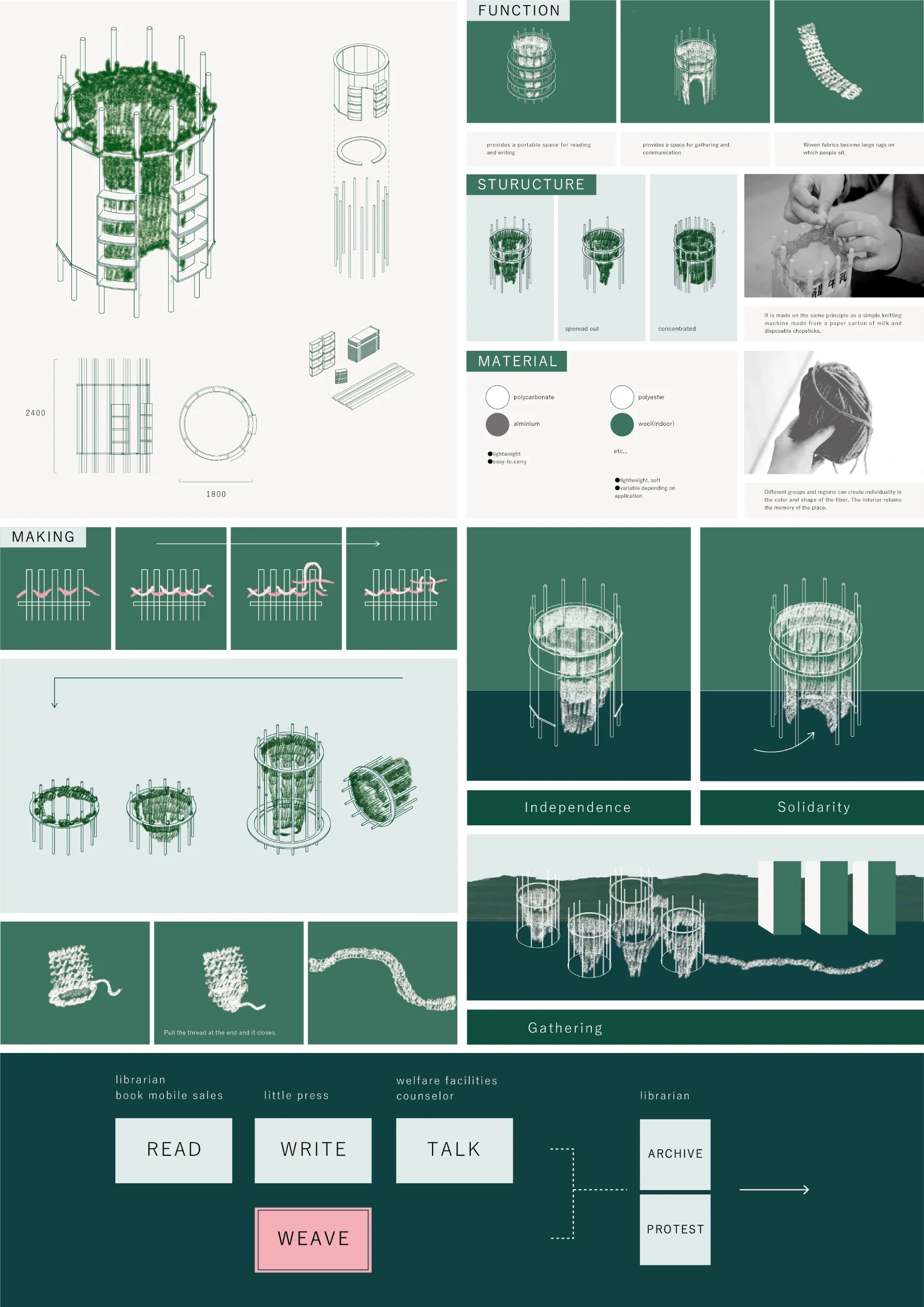

Thermos Balloon

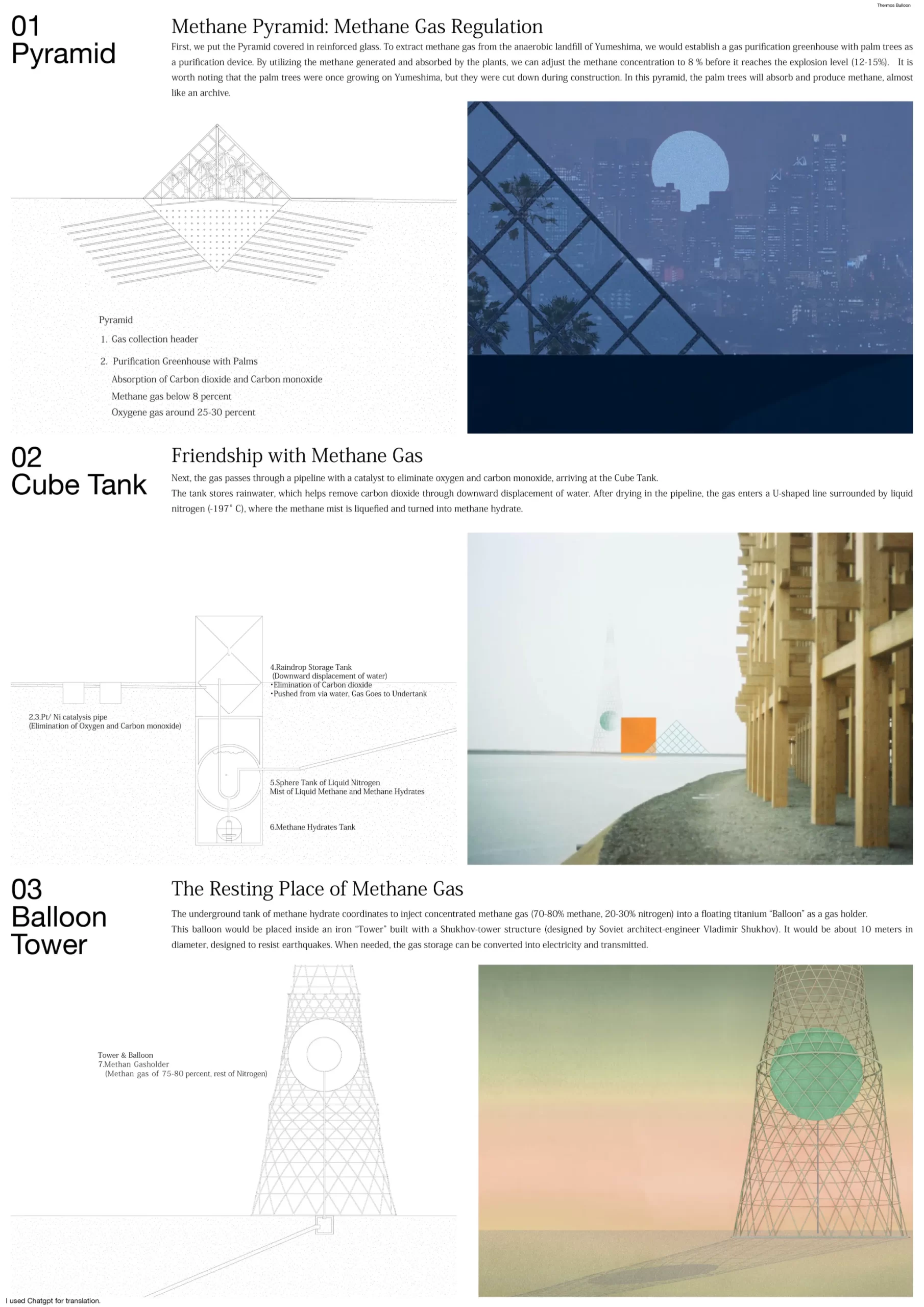

This project addresses the global issue of methane gas generated from landfills by proposing a solution that merges both architecture and infrastructure. The "Thermos Balloon" aims to transform methane, a harmful byproduct, into a valuable resource while minimizing environmental impact.

The design consists of three main components: a pyramid for collecting methane, a cube for creating methane hydrate, and a sphere to store the methane. This design is scalable and can be applied to other cities dealing with similar landfill issues.

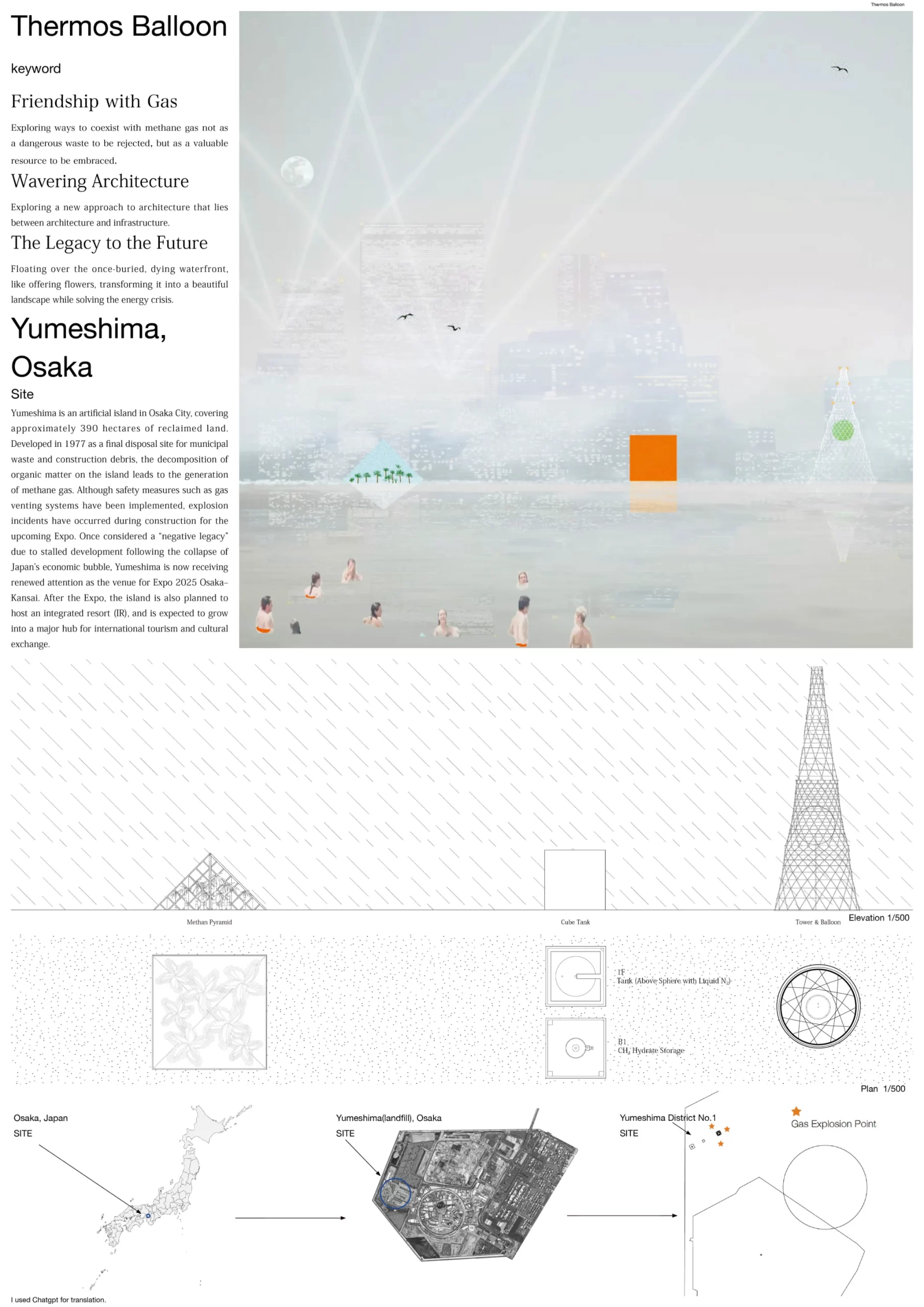

The concept was inspired by my experience in a landfill ecosystem workshop. I was struck by the large gas holders along the coast and the fear they invoked. I imagined the spheres rolling, crushing houses, and leaking gas. However, I thought that if these spheres floated in the air, they could transform from a frightening presence into a poetic landscape.

The site I focus on is Yumeshima, an artificial island in Osaka, currently being developed for Expo 2025, with plans for a casino after the event. However, methane explosions occurred in 2023, and there remains a risk of explosions on the island today. This problem of methane gas is common in many coastal cities across Asia, where land reclamation has been used to expand urban areas. As landfills increase, methane generation is inevitable, contributing to both global warming and explosion risks.

Cities have an inherent structure that produces methane: they collect, consume, discard, and bury resources. This leads to the question: What role should architecture play in this system? Rather than rejecting this system, can we elevate it through architecture?

The Thermos Balloon is my proposed solution. This system offers an infrastructure and architectural design that functions not only as a solution for Yumeshima but also for other cities facing similar challenges. The pyramid collects methane from the anaerobic landfill, the cube generates methane hydrate, and the sphere stores the methane. This design transcends time and place, providing a scalable solution to the growing methane problem.

The Thermos Balloon is a "poetic redesign" of infrastructure, transforming waste into energy and creating a system that is sustainable and scalable. This is not just a vision for one location, but a proposal for cities globally.

The program consists of several stages:

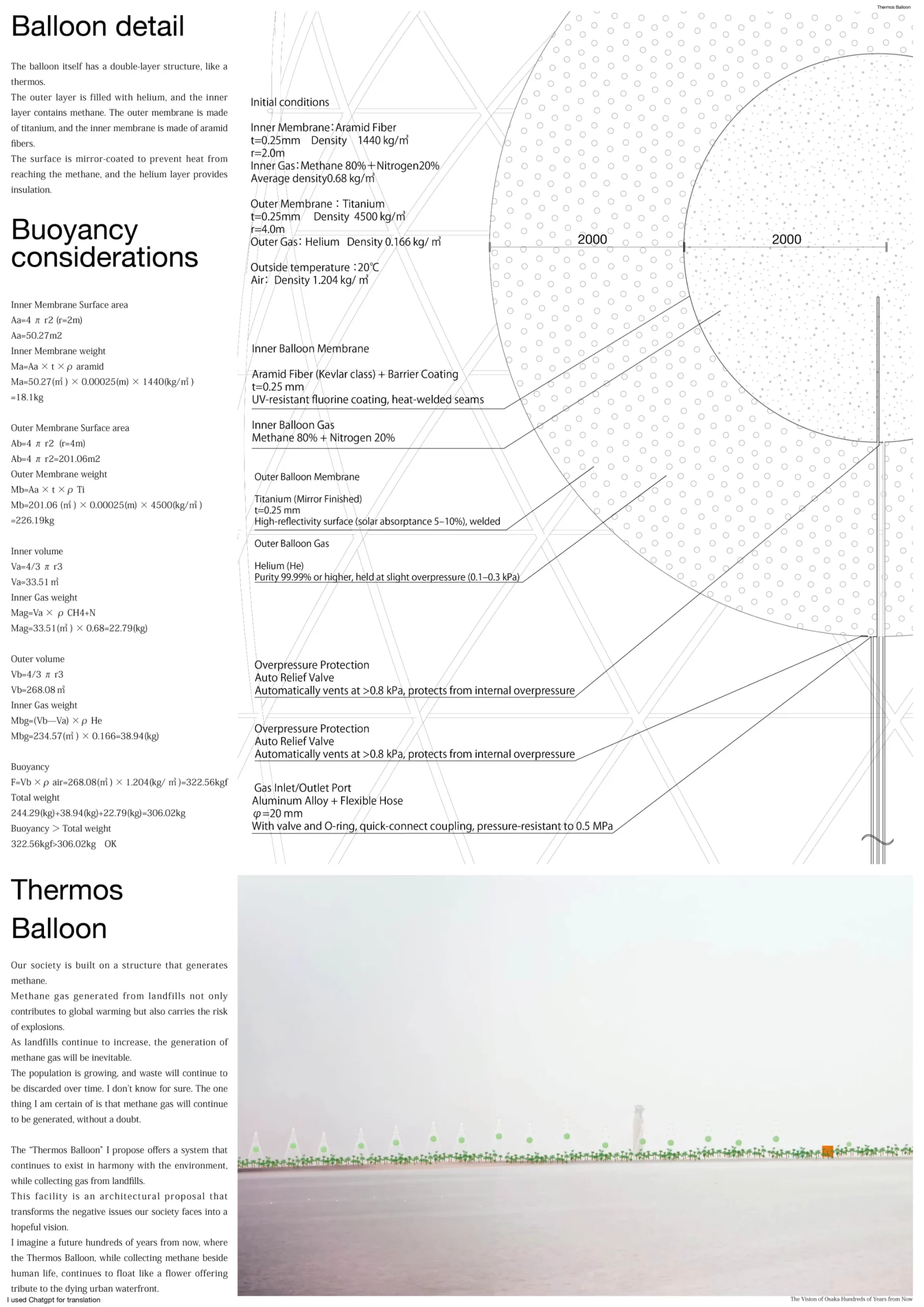

The floating balloon itself has a double-layer structure, like a thermos, where the outer layer is filled with helium, and the inner layer contains methane. The outer membrane is titanium, and the inner membrane is made from aramid fibers. The surface is mirror-coated to prevent heat from reaching the methane, and the helium layer insulates it.

This facility is fully automated, with no human intervention required. The Thermos Balloon represents an innovative approach to managing methane, turning landfills into energy hubs while minimizing environmental damage.

Methane is a silent contributor to global warming, and as landfill waste continues to grow, so will the generation of methane gas. The one thing I am certain of is that methane gas will continue to be generated, without a doubt.

The Thermos Balloon provides a system that works in harmony with the environment, collecting methane and transforming it into a valuable resource. It is not only an architectural solution but also a vision for a future where architecture plays a critical role in solving the environmental challenges we face. I envision a future hundreds of years from now where the Thermos Balloon, while collecting methane alongside human life, continues to float like a flower offering tribute to the dying urban waterfront.

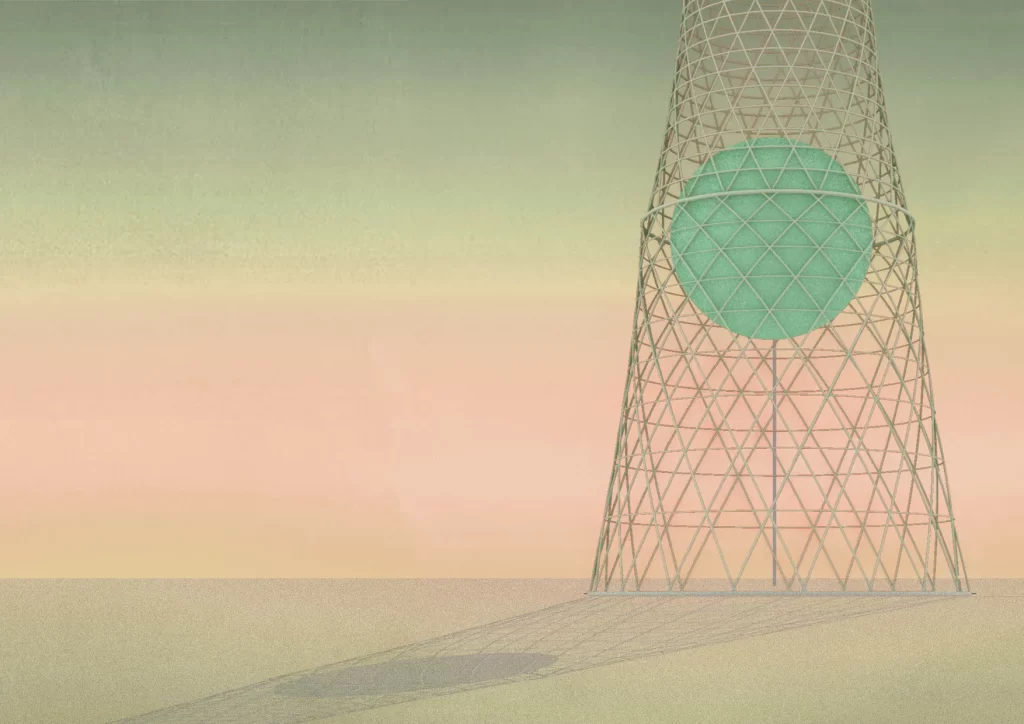

Amputation and Adhesion ~Creating new spaces using the traditional construction method 'Hikiya' ~

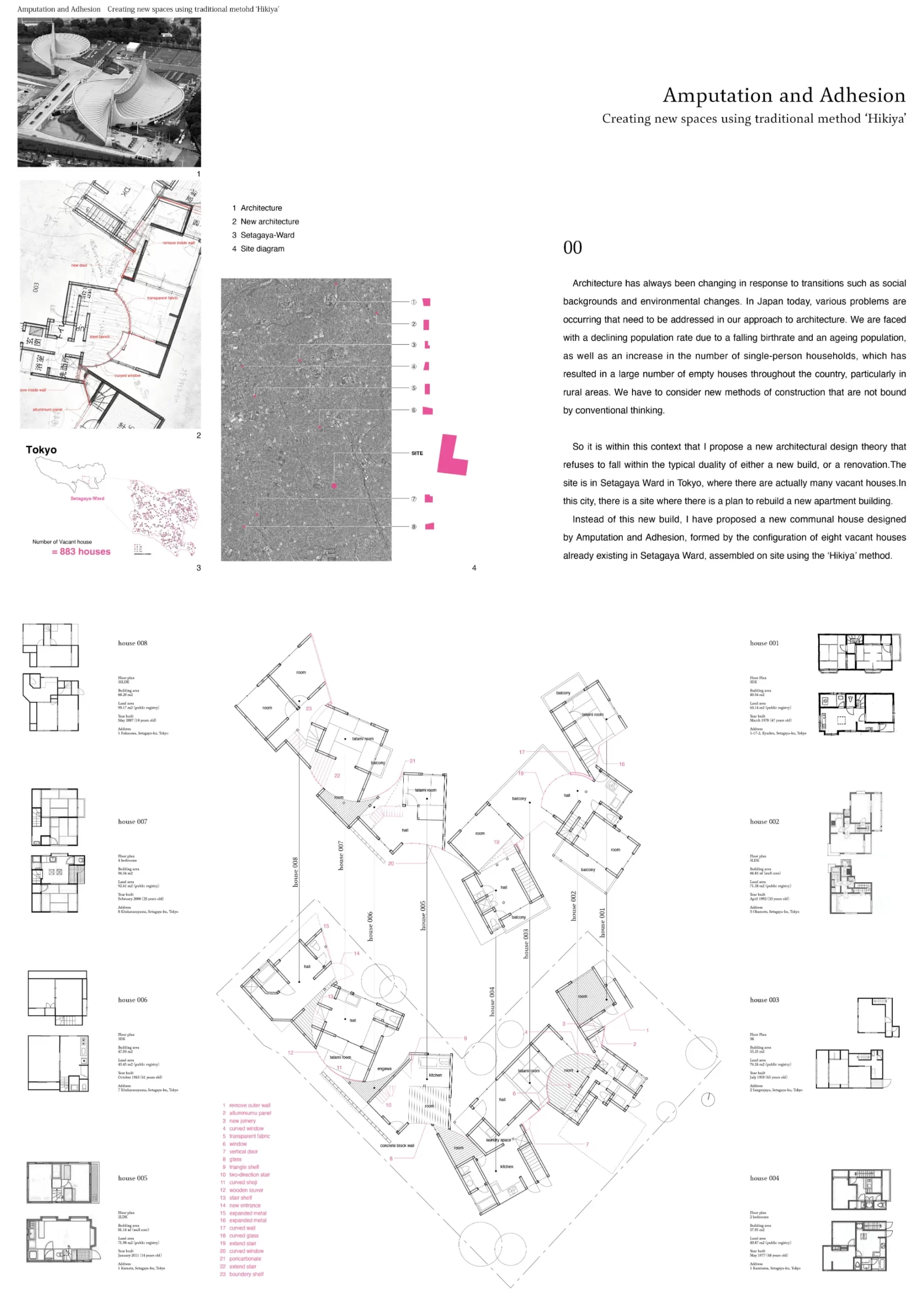

Architecture has always been changing in response to transitions such as social backgrounds and environmental changes. In Japan today, various problems are occurring that need to be addressed in our approach to architecture. We are faced with a declining population rate due to a falling birthrate and an ageing population, as well as an increase in the number of single-person households, which has resulted in a large number of empty houses throughout the country, particularly in rural areas. We have to consider new methods of construction that are not bound by conventional thinking.

So it is within this context that I propose a new architectural design theory that refuses to fall within the typical duality of either a new build, or a renovation.

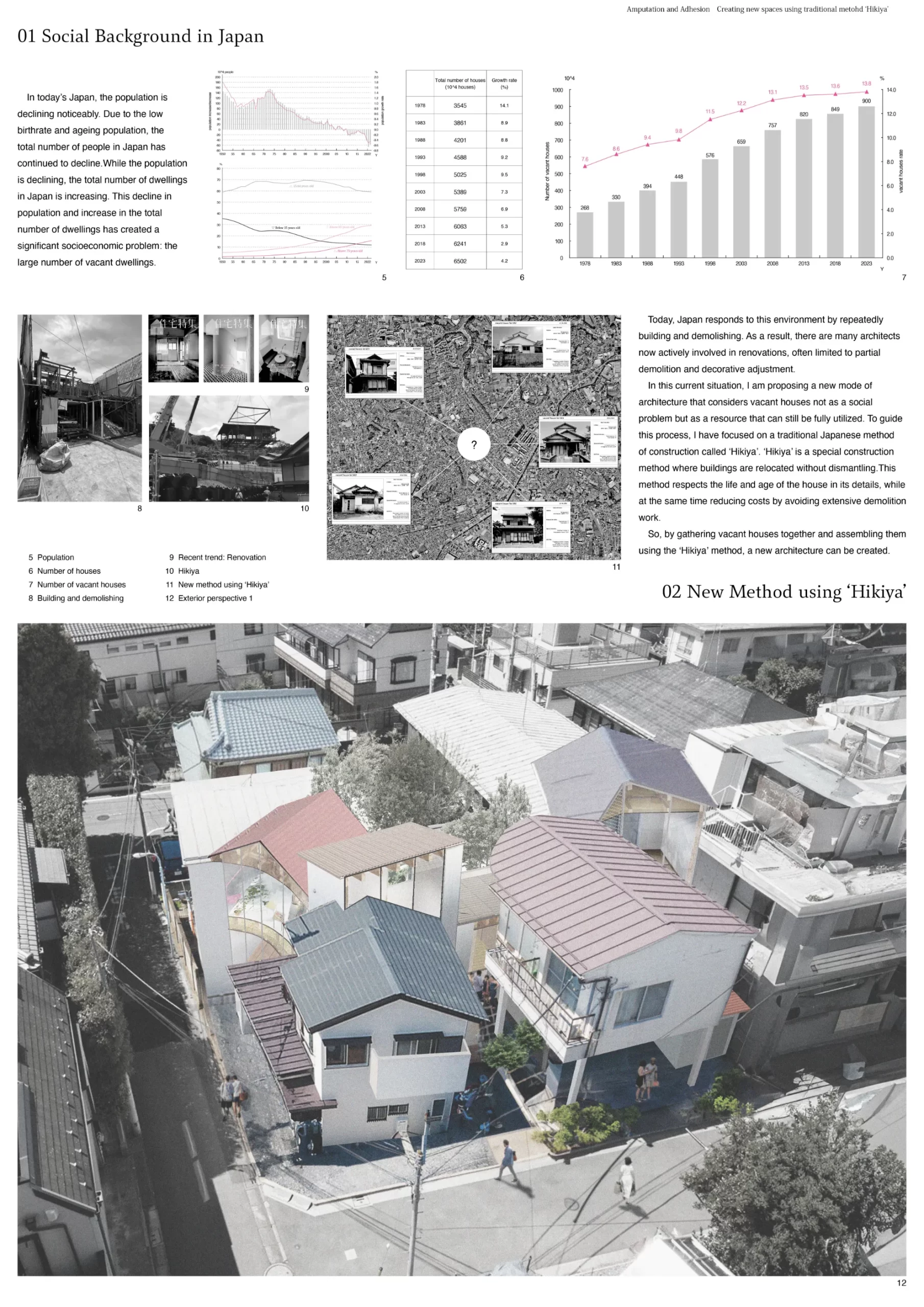

First of all, I will explain the current situation in Japan. In today's Japan, the population is declining noticeably. Due to the low birthrate and ageing population, the total number of people in Japan has continued to decline over the past seven years alone, with a decrease of more than two million people. While the population is declining, the total number of dwellings in Japan is increasing. This decline in population and increase in the total number of dwellings has created a significant socioeconomic problem: the large number of vacant dwellings scattered throughout the country.

Today, Japan responds to this environment by repeatedly building and demolishing. This culture of crash and build is predominantly controlled by economic pressures to build new, and by the issue of inheritance tax that makes it more viable to demolish and build again. As a result, there are many architects now actively involved in renovations, which has created a recent trend of conservative, somewhat superficial renovations, often limited to partial demolition and decorative adjustment. In this current situation, I am proposing a new mode of architecture that considers vacant houses not as a social problem but as a resource that can still be fully utilized. To guide this process, I have focused on a traditional Japanese method of construction called 'Hikiya'. 'Hikiya' is a special construction method where buildings are relocated without dismantling. Only the foundations and external walls are removed as required, and the structure is moved as it is. This method respects the life and age of the house in its details, while at the same time reducing costs by avoiding extensive demolition work. By retaining the structure and framework of these buildings, it is also a form of cultural preservation, by continuing the life of the craftsmanship inherent in Japanese building culture. So, by gathering vacant houses together and assembling them using the ʻHikiyaʼ method, a new architecture can be created.

The 'Amputation and Adhesion' method is proposed as a design method for assembling vacant houses. Defects are often considered negative 'drawbacks' due to the cost of repair and partial demolition, but here such defects are seen as a positive resource, and cut out to be retained in various ways. Specifically, this method involves cutting out the missing or ‘sick’ parts of a vacant house, and then gluing the cut surfaces of another house together to complement each other in new spatial arrangements. I came up with a variety of patterns on the plan, such as a straightforward pattern that follows the grid of the house, a pattern with a diagonal penetration that dares to betray the existing structure, or a pattern in which curves are inserted as a completely different language. Through the combination of these patterns and new configurations, a new spatial experience is formed that creates a sense of mystery and delight to the people who live there.

After the initial reconfiguration, furniture and new materials called bond elements are inserted as tools to solve the discrepancies that occur at the moment of joining. These could take the form of a mysterious staircase that connects different storey heights, or a transparent fabric used for a new type of partition, or a built-in shelf as a new way to form a boundary. The accumulation of these disparate elements and unique configurations bond together architecturally, which is at once symbolic of this new method of architectural preservation.

In reality, I will now talk you through a case study that I developed using this method. The site is in Setagaya Ward in Tokyo, where there are actually many vacant houses. In this city, there is a site where there is a plan to rebuild a new apartment building. Instead of this new build, I have proposed a new communal house designed by Amputation and Adhesion, formed by the configuration of eight vacant houses already existing in Setagaya Ward, assembled on site using the hikiya method. This is the floor plan. Let me explain the configuration

It has the overall appearance of a narrow residential area in Japan, but at the same time has a new face. The exterior exposes the section of the vacant house as it is in place. This creates a shocking façade that was not present in the existing elevation. Furthermore, the sections, which are both amputation and adhesion, lead the visitor to ponder the invisible after images, such as the contours of what should have once been or the life that was lived there. While the house has a variety of visual attractions through its clear-cut methods, it also has another curious attraction that leads us into the world of the invisible, the world of the imaginary. This is the spatialization of my new architecture method, that critically addresses the socioeconomic issues we are currently faced with in Japan, while also realizing a new spatial experience, that is more attune with the current times.

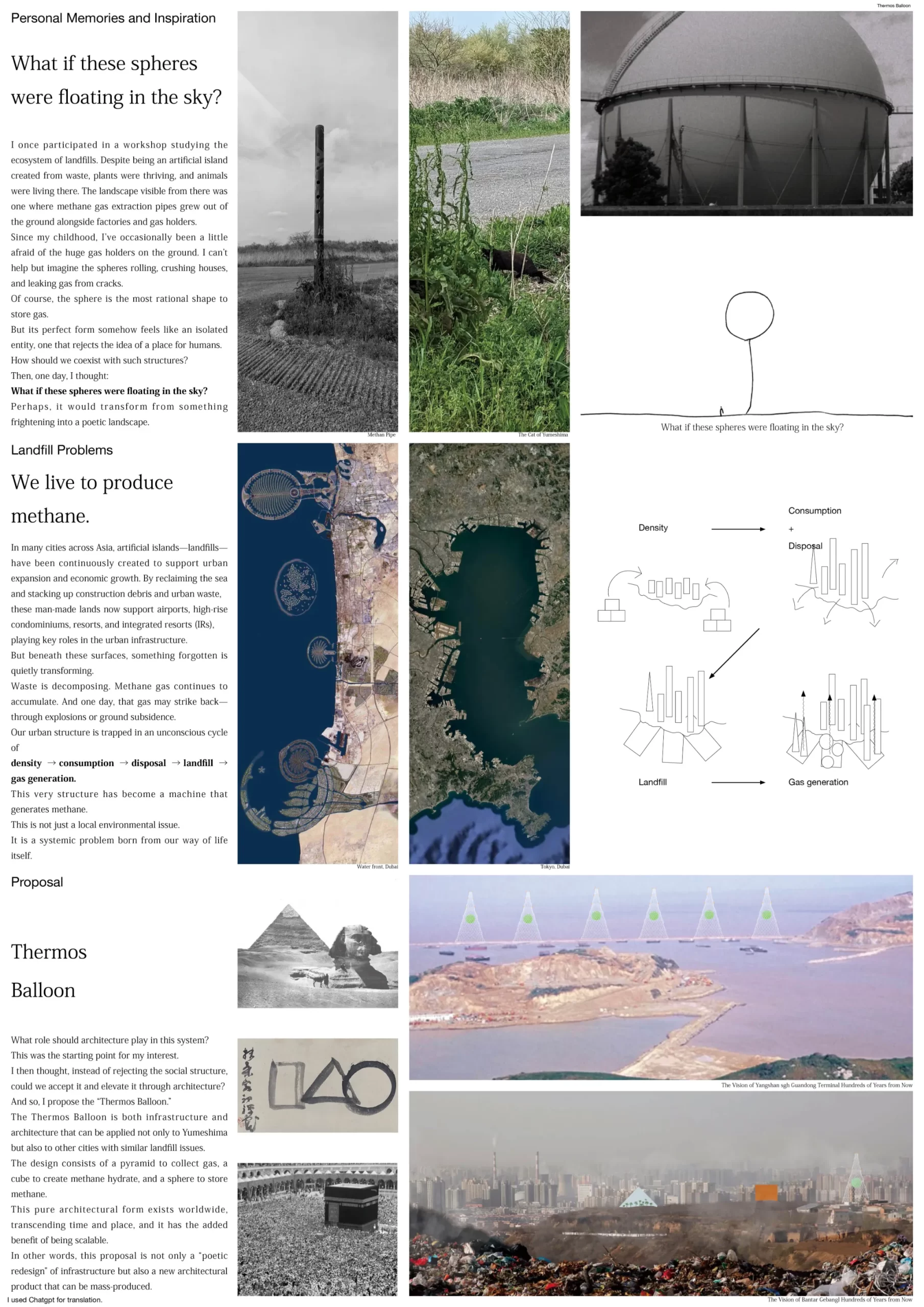

Restarting Space

Our cities are currently shaped by a controlling system that limits our potential, controls our behaviour, separates people, and distances us from nature. However, instead of giving up on the system, we should strive to develop a symbiotic relationship with our built environment to move forward and imagine a new future. To achieve this, we must accept the status quo but also critically examine our cities.

By looking at the gaps in our cities, we can discover new possibilities. While our cities today exhibit division and separation in buildings, communities, and relationships, there is potential for positive change by creatively exploring these gaps. Nature can flourish, personal exploration can thrive, and new urban development opportunities can arise. In order to tap into this potential, we need a framework for creating a system that is neutral, without ownership or authority, and capable of nurturing future possibilities.

One possible framework is the reinterpretation of the grid. By overlaying a rectilinear grid over the city, the overlaps of the gap spaces within the built environment can reveal a new form. This form would emerge by chance, originating from the rational grid's overlap with the lived realities of the gaps. It would transcend human design, resembling something closer to the wild—a form that is anti-urban in its organisation and organic in its origin from the conditions of the gap spaces.

Another source of inspiration for this proposal is the idea of a monolith. The overlapping of the grid and gap spaces gives rise to an organic form that can be best expressed as a monolith—a slab-like architectural element. To achieve sustainability, the slab is constructed using concrete reinforced with carbon nanotubes, a lightweight material that is approximately 20 times stronger than steel. The monochromatic black colour of the carbon signifies its lack of ownership.

Three different patterns have been developed based on the elevation of the grid, the size of the mass, and the objects to be hollowed out. The "field" pattern connects several buildings to create a positive community space, such as a plaza or park. The "branch" pattern emerges from the complex connection of alleyways, fostering random encounters and exploration. The "archipelago" pattern consists of multiple small places that reflect the relationships between neighbours, allowing for individuality, diversity, and creativity to flourish.

These slabs offer solutions to various problems, both large and small. On a personal level, they can extend the usability of balconies or patios, providing larger floor areas for activities and gatherings. From a broader social perspective, the slab system can address urban challenges in disaster-prone regions like Asia. The carbon nanotube structure of the slabs enables them to withstand floods and earthquakes, serving as evacuation spaces and shelters during disasters. Additionally, the slabs can contribute to sustainability by incorporating transparent thin-film solar cells into their design, generating renewable energy and supplying it to the surrounding buildings and community.

By filling the slabs with soil and planting trees and plants, the gaps between cities can be transformed into green spaces, allowing for the coexistence of urban areas and vegetation. Over time, as buildings, grids, and natural elements weather and undergo demolition, the original form of the slab will emerge, standing alone and belonging to no one. This creates an opportunity for new cultures, architectures, and ecosystems to be born, reactivating the site of the city.

These spaces can become "places for a fresh start," stimulating people's creativity and imagination and creating new possibilities for our built environments.